by Advin Arnby Machata

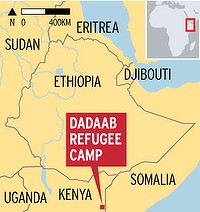

Dadaab, the 20-year-old refugee camp spawned by the Somali Civil War, has become a perpetual humanitarian disaster, with thousands of people malnourished, without shelter or any means of subsistence. Providing what little health care and social services there are in the camps still costs the Kenyan government and the international community hundreds of millions of dollars. Largely, it is a problem without a good solution.

While having generously accommodated the refugees for two decades, some Kenyan politicians have started to call more aggressively for repatriation after the surge of new refugees following last year’s famine. Sanctioning a military intervention into Somalia in order to establish safe havens suitable for relocation has been part of this. This in turn has been met with opposition from humanitarian agencies running the camps. While they argue correctly that a repatriation at this stage would likely increase insecurities for refugees and aid workers alike, they do not provide any constructive solutions of their own.

Indeed, the scale of the camp puts any type of solution to a tough test. Currently 500,000 refugees, mostly Somalis, inhabit five camps in an arid environment around a village that 20 years ago was home to a mere five thousand inhabitants. To put that into perspective, it’s as if the city of Liverpool in the United Kingdom grew to its current size from a sleepy unknown village in merely two decades.

See Also: Refugees in Uganda: A Burden or An Asset to the Host?

Integration?

Melanie Teff at the Guardian’s poverty matters blog suggested that the refugees living in Dadaab could be an asset in a comprehensive regional development plan. She points to the entrepreneurial spirit of many residents of Dadaab, and research by Cindy Horst, Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), and others have illuminated the many successful ways of coping with life in the camp. Like in most populations however, only a small number have had that little extra luck together with an entrepreneurial spirit to create something. The majority need jobs available for them to take part in a developmental project.

This is not to underplay the achievements of the camps’ entrepreneurs. A study by the governments of Kenya, Denmark and Norway estimated that as much as US$14 million is channelled into the region through the agencies in Dadaab, and that refugee entrepreneurs themselves turn over $25 million.

This may sound like impressive figures, but even when added together, and shared only among camp residents, not local Kenyans, it merely amounts to $78 per person. This is but a fraction of Kenya’s still low $1,800 GDP per capita, and it highlights a particular socio-economic characteristic of most late developers: they do not lack manpower, but capital.

Thus, from a developmental stand point, it seems hard to argue that manpower-rich, capital-poor Dadaab has any value to add to a national Kenyan economic project, it merely dilutes the government’s scarce capital resources.

Except for the tough job of funding a comprehensive regional development plan, there are important political obstacles. Before its civil war, Somalia had difficult relations with its neighbors. It occasionally laid claim to Somali inhabited territory beyond its borders, notably in the Ogaden war with Ethiopia in the 1970s and a proxy war in Kenya (the so-called Shifta war). Kenya is worried that if it integrated a great number of additional Somalis in its east, similar future claims may seem more plausible and be supported by a ‘fifth column’.

See Also: Urban Refuge: Boston students create an app for refugees in Jordan

This worry and the perception of Somali immigrants as taking jobs and drawing a disproportional amount of humanitarian aid is also fueling strong racist sentiments towards the immigrants. A 2009 Human Rights Watch report, entitled From Horror to Hopelessnes, detailed some racist abuse faced by Somali immigrants in detention in Garissa:

“When we arrived, the police made us line up facing a wall and said we should ‘think about never coming back to Kenya’. Then police officers hit all of us three or four times on the back and head with a stick. That night the Kenyan men in a cell next to ours, which was separated only by bars, urinated in plastic bags and threw them at us and cursed at us in Swahili all night long. We complained to the police but they did nothing to stop them.”

Repatriation?

However, even while integration in Kenya seems difficult, repatriation is no less challenging. In spite of Kenya’s claims that their incursion has secured southwestern Somalia from Al-Shabaab—the Islamist militia that for many years controlled much of southern Somalia—civilians continue to flee the area rather than returning.

There are many second and even third generation refugees in the camps that have nothing to return to in Somalia. Also, many more recent refugees have no close family left across the border, and most who used to own property that served as a means of subsistence had these destroyed or violently appropriated.

Without support to re-integrate back into Somali society, it is likely that a great number of immigrants would become internally displaced persons (IDPs). Merely rebuilding the Dadaab complex 100 kilometers east makes little sense—not even for Kenya, as it would still be a hotbed for terrorist recruitment but with easier access for Al-Shabaab operatives.

A sudden influx of refugees into the politically and economically fragile Somalia could have devastating effects on the situation. Conflicts over repossessed land and livestock would be likely, which would feed into the conflict between the Somali government and Al-Shabaab.

The continuing insecurity and the lack of opportunities across the border means that voluntary compliance is highly unlikely, and without it repatriation is not really an option. Moving the entire population of a large city by force would require too many of Kenya’s police and military forces, leaving other regions and possibly safe-zones in Somalia with inadequate security. It would also violate the 1951 refugee convention, bringing international condemnation and possibly sanctions onto Kenya. With an election year looming, it is likely that tough calls for repatriation are more a call for votes than actual desired policy.

Solutions?

Considering that the staggering challenges with both integration and repatriation are made more difficult by the great number of individuals that need to be taken into account, both integration and repatriation must be employed in a medium to long-term, regional, cross-border development strategy. A third option, not explored in detail here, is resettlement to a third country, which has been, and should continue to be, pursued for as many as possible who are willing.

There are also some positive aspects to the situation. As there are significant numbers of Somalis permanently settled in Kenya since before independence, the Somali clan system could be used to have distant relatives help integrate Somali refugees out of clan solidarity. And, as IRIN reported on the 15th of June 2012, there is some political support for the integration of a smaller number of refugees that have personal ties to Kenya.

In Somalia, the continued military offensive against Al-Shabaab has fueled some optimism that the main violent threat may soon be defeated. The appointment of the moderate Hassan Sheikh Mohamud to the presidency gives Somalis a more neutral figure to unite behind. Still there is a long way to go for peace and stability.

The combined integration, repatriation and resettlement of the refugees need a lot of time, money, political will and long-term security in order to succeed.

(This article originally appeared in the October 2012 issue of Global South Development Magazine that focused on inspiration. You can download the issue for free: here)