By Najibullah Gulabzoi & Mohammad Shoaib Khaksari

In September 2015, the Government of Afghanistan adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. While taking into account the existing capacity and resources of the Government of Afghanistan, the Ministry of Economy (MoEc) launched the SDGs with the commitment to effectively embed the global goals and targets in national and local plans and processes. These efforts were ultimately aimed at making SDGs serve as the basis of all national development strategies and plans in Afghanistan. The Ministry of Economy worked with over 28 different government agencies to translate the global goals and targets into a nationally owned framework that considered and reflected Afghanistan’s ambition, capacity, resources and the complexity against which Afghanistan had to deliver on the 2030 Agenda. In short, Afghanistan knew where it was going and the Afghanistan SDGs framework provided a local compass on the road to 2030.

However, COVID-19 has constrained many of the ongoing SDG-readying support provided to the Government of Afghanistan and may have major implications for judicious and long-term development policymaking and programming that are needed to achieve the priority SDG targets in Afghanistan. A confluence of other events—like the surge in the ongoing conflict, the US military withdrawal and a significant further decline in foreign aid and military spending—has already forced the Afghan government to focus more on immediate and urgent political challenges rather than committing to long-term policies for reforms, poverty reduction and sustainable economic growth. This situation has already made some of Afghanistan’s key international partners to raise their concerns on the reported slowdown in the Afghan Government’s anti-corruption reform efforts.[1]

It is also important to recognize that this will ultimately bring political and security objectives as well as addressing urgent humanitarian needs emanating from COVID-19 into sharper focus in the minds’ eyes of the Afghan leaders and the donor community in Kabul. Therefore, the paper argues that the systemic disruption caused by COVID-19 compounded by the already existing “short-termism” will seriously hinder many of the long-term planning and programing needed for Afghanistan SDGs by crowding out attention and resources from long-term policy objectives to short-term humanitarian and other ex-ante interventions designed with haste.

We also argue that Afghanistan is already off track for achieving most of the priority A-SDG targets and the level of effort required to achieve A-SDGs can only be made possible if Afghanistan can mobilize significant additional financial resources and commits itself to an evidence-informed, coherent and long-term reform and development program. Ideally, and in the medium-to-long-term, these policies need to be informed by reliable assessments of the impact of COVID-19, the dynamics of the ongoing conflict and, potentially, the decreasing interests of donor countries to make long-term investment commitments in Afghanistan.

How COVID-19 disrupts Afghanistan SDGs?

Latest projections indicate that GDP growth in Afghanistan is likely to decline by 8.2 percent in 2020.

Continued and equitable economic growth is a prerequisite for sustainable development and the achievement of many, if not all, SDGs in Afghanistan. The disruptions caused by the COVID-19 in the regional and international supply chains and the eight-week long quarantine measures implemented in the months of April and May by the Government of Afghanistan have negatively impacted GDP growth in the first and second quarters of 2020 and significantly contracted economic activity across the country (SDG 8.1). Latest projections indicate that GDP growth in Afghanistan is likely to decline by 8.2 percent in 2020.[2] This contraction will significantly reduce the real GDP per capita and given the rise in violence across the country, coupled with the political uncertainty in part due to the engagement of international community in Afghanistan, the projections for the recovery of economic activities by 2021 may prove hard to hold.

COVID-19 seriously affected trade. Afghanistan’s exports dropped to just US$ 32.7 million from a reported $204 million in the beginning of 2020.[3] With an adversarial trade situation, especially considering the bilateral relations between Afghanistan’s immediate trade partners—Iran and Pakistan—the recovery of pre-pandemic export levels may not be possible in just one to two years. These will negatively affect and further expand the demand-supply gap in Afghanistan with repercussions for almost all of Afghanistan farmers, processors and consumers. Also, price inflation almost doubled and government revenues declined significantly—with direct implications for government spending on health, food security, poverty alleviation and other critical government services.[4]

The negative impact of this contraction is also projected to cascade to other indicators, potentially negatively affecting prospects for job creation and employment in Afghanistan. One projection estimates that the 8 percent decline in GDP could increase the unemployment rate by 14 percent (from 23.9 percent to 37.9 percent). However, it must not be forgotten that underemployment is more acute than unemployment in Afghanistan. Most of the “jobs” that are classified as full employment are periodic and are often not readily and regularly available. Therefore, the GDP contraction projects that by the end of 2020, 4.8 million people could be unemployed and underemployed.[5]

Though the COVID-19 impact on the Afghan economy is projected as a short-term shock–with most of the deceleration projected to recover in the space of one to two years—the cascading negative impact on other SDG targets, such as those on unemployment, loss of savings and income, and increasing household expenditures on health could linger for years. Combining the experiences from previous systemic shocks to the Afghan economy could prove that this pattern actually exists in Afghanistan. For example, economic activity never recovered to the pre-crisis levels when the GDP contracted significantly after start of the withdrawal of international troops and the fiscal crisis in 2014. In a similar way, the unemployment rate almost increased by double-digits—jumping from 13.5 percent to 22.0 percent in the aftermath of these crises and never returned to pre-crises levels.[6] These do indicate the sustained and deteriorating effects on the labor market and economic performance in Afghanistan once crises hit hard and the path to recovery seems, at least in Afghanistan, slow and arduous. Therefore, the catchphrase of “recovering and building back better” without considering and bringing to light the cascading effects on most interlinked SDG targets could be much slower in the Afghanistan context than projected. The path to recovery is much harder than projected.

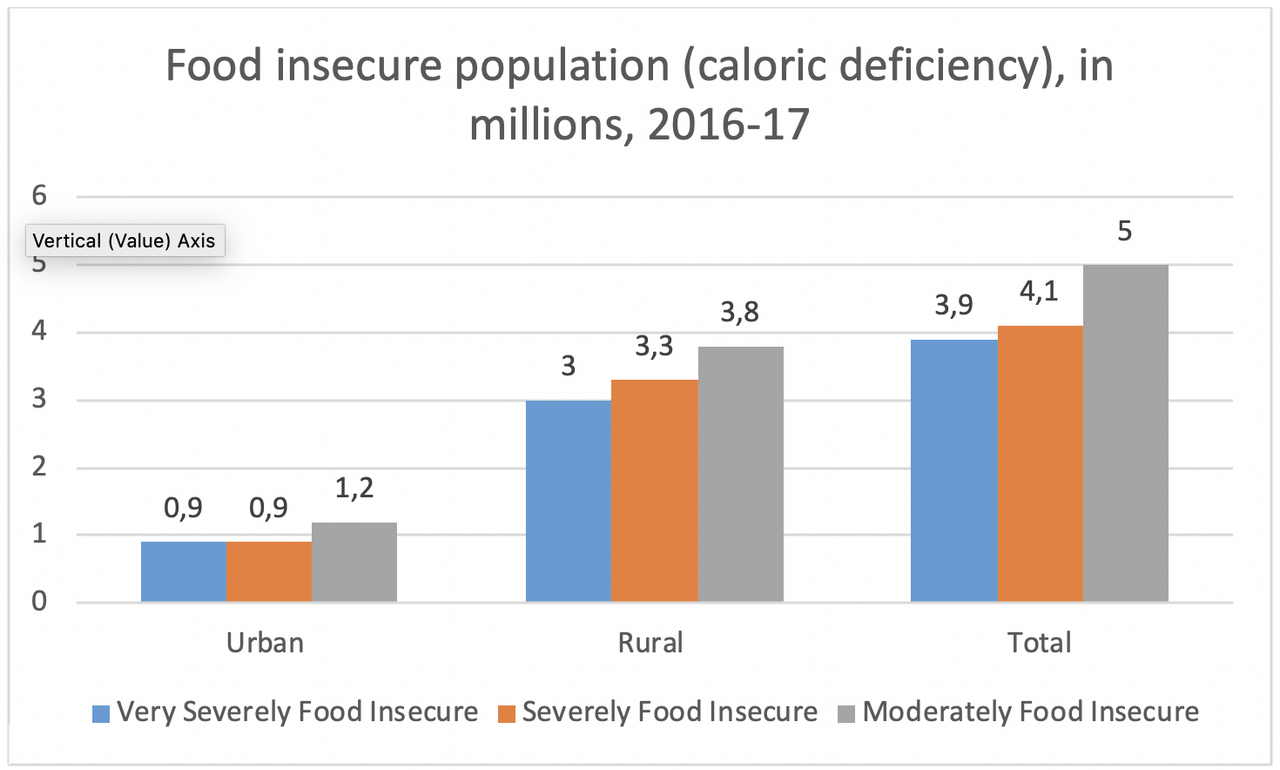

Most estimates and projections show that COVID-19 has also caused significant decline in welfare standards and that they are worse off for a large number of Afghans. A recent study by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford and UNICEF Afghanistan revealed that many of the deprivations as measured through the multi-dimensional poverty index (MPI) have increased as a result of COVID-19 pandemic in Afghanistan. As a combined and integrated poverty measurement tool, the MPI is relevant to many SDGs, most importantly to SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Eliminating Hunger) SDG3 (Good health) SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender equality), SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth) and SDG 10 (reducing inequality).

The researchers have shown that the incidence of multi-dimension poverty would increase from 51.7 percent to 73.5% as result of the COVID-19 spread in Afghanistan.[7] Relying on the data from Afghanistan Multi-dimensional Poverty Index (A-MPI), the researchers analyzed Afghans’ vulnerability to the COVID-19 pandemic to show the immediate health risks and threats to the most vulnerable Afghans. The researchers have also relied on the A-MPI to conduct “micro-simulations” in an effort to measure how COVID-19, and the response measures to it, has disrupted socio-economic indicators. In addition to increase in the multi-dimensional poverty in Afghanistan, the report also indicates that the majority of Afghans at risk of COVID-19 are multi-dimensionally poor. The report shows that 75.7 percent of Afghans are in vulnerable employment without social protection and other safety nets.[8] These workers are vulnerable because of informal work and the lack of social protection and safety nets, offered either through the private sector or through the government.

The increase in the deprivations as shown by Afghanistan multi-dimensional poverty index because of COVID-19 directly affects a large number of SDG targets. For example, the increase in deprivations could directly and negatively affect SDG 4.1 (access to quality education), SDG 8.5 (achieve full and productive employment), SDG 8.6 (proportion of youth not in employment, education or training). These will, in turn, negatively affect addressing SDG 1.2 (extreme poverty), which the World Bank has projected to increase to 72 percent due to COVID-19.[9]

Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a short-to-medium term systemic disruption to the SDGs in Afghanistan. At issue is not only how deep and wide the impact is to the health sector but the extent to which this disruption has cascaded to social, economic and governance systems as a whole. Therefore, it becomes important to analyze these cascading effects across different systems to gain a better understanding of the lingering impact of COVID-19 on A-SDGs.

Although Afghanistan does not have any SDG target with a 2020 deadline, COVID-19 will reverse the progress Afghanistan has made on SDG3.[10] The Afghan public health system is already struggling to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in the country. Many centers for COVID-19 are overwhelmed and patients, out of desperation, have even used a “treatment” reportedly developed by an Afghan “herbalist” from “several types of opiates—opium, morphine, papaverine, codeine—mixed with a few herbs.” [11]

COVID-19 will disrupt provision of basic health services across the country with negative effects on maternal and child health. The need to almost entirely dedicate government capacity to life-saving operations and to increase spending on COVID-19 will also result in a drop both in quality and quantity of other limited health services available for Afghans. Given the scale of corruption in the public health sector[12] and the reported theft of equipment and misuse of public funds allocated to the COVID-19 emergency, it is far-farfetched, if not outright naïve, to believe that the attention and resources allocated to the public health sector for dealing with the COVID-19 crisis will have any long-term positive impact.[13] With the ongoing restrictions on international travel and cross-border movement, thousands of Afghans, who sought medical treatment in India, Pakistan and other countries, are less likely to receive treatment and health care but they further strain an already fragile health system beyond its limits.

The closure of schools is the immediate impact on children and young people in Afghanistan.

The spread of COVID-19 and the resultant acute deficit of health care services will, in turn, deteriorate many other social SDG indicators in Afghanistan—serving as a rapid feedback loop in disrupting exacerbated social services. The closure of schools is the immediate impact on children and young people in Afghanistan. Although the Afghan government promised that the closures would not affect learning because they would compensate through “online platforms,” even a partial transition to digital learning remains a distant dream for a majority of students. If online classes are offered, at some point, accessing them will be difficult for most of the poor and disadvantaged students because most of them cannot afford expensive digital devices and internet access in Afghanistan. The school closures have also negatively affected private schools across Afghanistan. Hundreds of private schools and thousands of teachers have lost their income and some of these schools are already permanently closed.[14]

A majority of Afghans work in the informal sector—mostly unskilled, uneducated and poor—without any social protection benefits. These sections of the population were directly impacted by the disruption in economic activities when the Afghan government implemented the lockdown measures across Afghanistan. Lost and reduced incomes will continue to impact access to health services, education, food and may even translate in the loss of assets for those households remaining vulnerable to falling into poverty. Agricultural exports to neighboring countries and other export corridors have already been negatively impacted due to border closures and the overall trade disruptions. The overall impact on economic growth will further exacerbate the already overstretched fiscal resources of the Afghan government for providing health care services, adapting and compensating for the loss of learning through successfully transitioning to digital learning and addressing humanitarian needs, such as provision of food and medical supplies.

Why COVID-19 is a “threat multiplier” for A-SDGs?

Conflict and fragility have already made committing to and investing in promising long-term development goals unattractive both to the Afghan government and the development community. Instead, most development projects have focused on producing and reporting immediate results often with limited accountability demanded and attention paid.[15] The issue-based nature of these development projects often made it impossible to measure their long-term impact or their contribution toward long-term development goals. Many of these short-term interventions were devoid of any fundamental understanding of the social context and a dearth of socio-economic analysis made them susceptible to failure. However, the lack of security, fragile, weak and corrupt institutions justified financing these small-scale, short-term and one-off interventions undertaken by various non-governmental development actors in highly unpredictable environments. One of the greatest challenges was monitoring and reporting on these initiatives.[16] After nearly two decades, the results of these piecemeal and short-term development interventions remain partial at best.

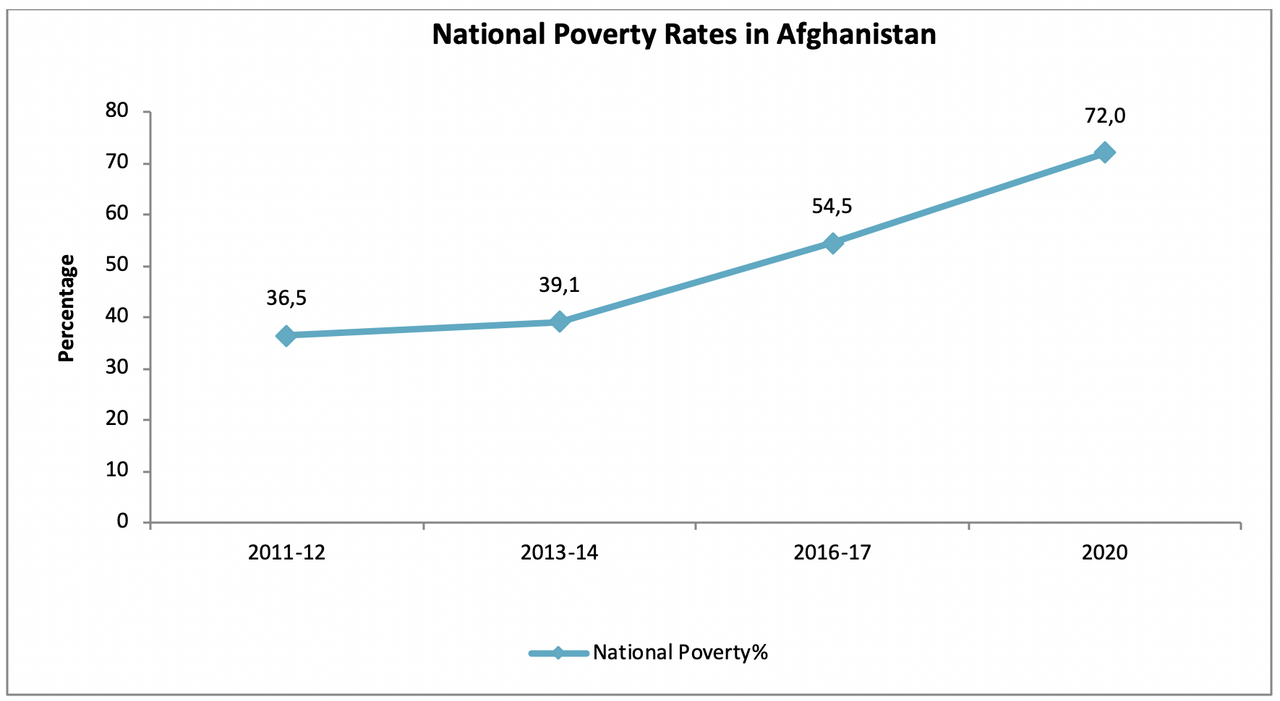

Despite billions of dollars that poured into Afghanistan in the form of foreign aid and military spending, poverty is soaring in the country.

Despite billions of dollars that poured into Afghanistan in the form of foreign aid and military spending, poverty is soaring (estimated even higher than in 2003 when foreign aid had just started flowing into the country after the Tokyo Conference on Afghanistan), social inequality is at its peak with record unemployment.[17] With declining donor interest in Afghanistan, many claim that the US peace deal with the Taliban is seen as an “out of jail card” for most donor countries to cut costs.[18] The World Bank, however, has already warned that Afghanistan will need near current levels of foreign aid (around USD 7 billion a year) even after a peace agreement is signed with the Taliban to maintain core government functions and “post-settlement programming initiatives.”[19]

Add to these the combined, and potentially medium-term, effect of COVID-19 and it will not be so difficult to argue that these challenges will complicate proper planning and financing of SDGs in Afghanistan. The Afghan government is currently struggling with financing the health emergency and humanitarian problems that the COVID-19 pandemic continues to pose for Afghanistan. Considering the global financial and economic havoc that the pandemic has caused so far, it is, however, highly likely that there would be significant declines in ODA levels to most developing countries, including in Afghanistan, as most international donors focus on domestic challenges that COVID-19 has created across the developed world. Mobilizing finance, not just ODA, will therefore be the greatest challenge for planning and achieving the SDGs in Afghanistan as the government and its development partners allocate scarce resources to acute humanitarian needs that COVID-19 crisis is creating across Afghanistan. Therefore, many of the long-term planning processes, including mobilizing finance for A-SDGs from innovative and new sources, will be seriously disrupted as the focus of Afghan government and its development partners will shift to humanitarian needs, often addressing them through quick-impact interventions without any exit strategies. However, this decline in ODA may prompt an immediate action from the Afghan government and its development partners to explore innovative and sustainable financing instruments and resources for long-term socio-economic programs in Afghanistan.

In the absence of an evidence-informed and coherent development plan, and the necessary financing instruments already in place, that working toward interlinked and collective humanitarian and development outcomes through concurrent programming is easier said than done. Therefore, it would be very hard to address short-term humanitarian needs while keeping in sight the long-term development objectives. However, not reconciling the imperatives of humanitarian, development and peacekeeping objectives will result in outcomes that fail to facilitate the attainment of A-SDGs. This is a very tall order. The on-going conflict and an unexpected US military withdrawal—especially if the peace process with the Taliban turns into protracted negotiations—can trigger immediate security and political challenges for Afghanistan. These challenges will further disrupt planning for long-term reform and socio-economic programs. But a long-horizon, nexus-based approach is still needed as it is the only way toward sustainability.

Afghanistan is off-track on most SDG targets

Afghanistan has already regressed on many A-SDG targets. The proportion of people living below the poverty line—by both domestic and international measures–(SDG 1) has significantly increased in spite of billions of dollars of foreign aid and military spending in Afghanistan since 2002.[20] Afghanistan did prepare Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, but any quick review will show that they fall short of sound development strategies. Moreover, they remained just that—papers, actually piles of them after they collected anecdotes of short-term development projects to report progress. By one account even the data presented to show progress remain highly debatable.[21] They were never financed, nor were they monitored but tens of international and national experts worked to prepare and present them in international conferences on Afghanistan.

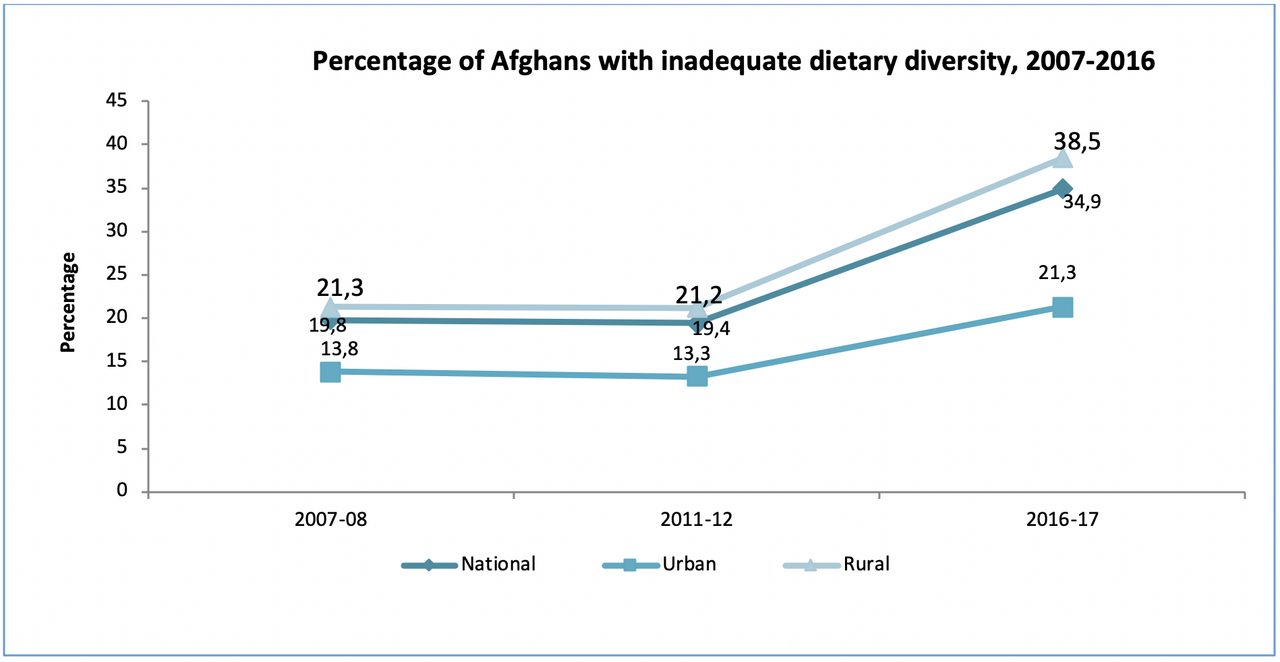

Source: Afghanistan Living Condition Surveys and World Bank latest projections[22]

Source: Afghanistan Living Condition Surveys and World Bank latest projections[22]

The Afghanistan economy grew rapidly until 2012 (with real GDP growth estimated 11.8 percent in 2012).[23] But this growth masks widening disparities between the poor and the rich in Afghanistan (SDG 10)—elites and their clients that enriched themselves on the international military largesse in Afghanistan while the majority of Afghans who remained underemployed and in precarious informal jobs or lost their jobs and families because of the conflict. Corruption is endemic and graft in the public sector is one of the greatest obstacles to development and equitable economic growth in Afghanistan. With huge public expenditures, particularly considering defense and security spending, the Afghan government institutions are mired in corruption and misuse of public funds (SDG 16).

Many of the reform initiatives implemented over the past two decades have yielded minimal results. Unemployment, underemployment and precarious work mostly in the informal sector remain great challenges to pulling communities out of poverty (SDG8) and the government policies on creating decent jobs for Afghans and addressing unemployment have been ineffective. In the absence of compelling policy initiatives, prospects for the long-term engagement of international donors in Afghanistan, including increased levels of ODA remain grim (SDG 17). Climate change—droughts, seasonal floods and other natural disasters—and rising pollution levels in many urban areas have put people’s lives and livelihoods at great risk (SDG 13). The health (SDG 3) and education (SDG 4) sectors were the only success stories that Afghanistan show for the nearly two decades of international development efforts. However, good progress made in these two areas were recently reversed by the COVID-19 pandemic as thousands of people are infected and hundreds more died from the virus while millions of children and youth are out of schools and classrooms.

COVID-19 has dealt a severe blow to development in Afghanistan. It can further reverse the progress Afghanistan has made over past two decades if the Afghan government fails to commit itself to an evidence-informed, sound and coherent development plan that holds the promise of bringing peace and also addresses the short-term humanitarian needs of Afghans through tapping into the collective capacity of the Afghan government and its international development partners.

[1]UNAMA, “Local Statement by the Ambassadorial Anti-Corruption Group on Good Governance, Anti-Corruption and Rule of Law,” UNAMA, Afghanistan, (July, 2020).

[2]Afghanistan Economic Outlook, Biruni Institute (July 2020), can be accessed from: file:///C:/Users/user/AppData/Local/Microsoft/Windows/INetCache/Content.Outlook/PO69EFO8/Biruni_Institute_AFG_Economic_Outlook_Issue2_July2020.pdf

[3]Ibid.

[4]Ibid.

[5]Ibid.

[6]The ALCS 2013-14 report made an effort to compare the data between NRVA 2007-08 and ALCS 2013-14 (crises years) by retabulating the former data sets by applying the same definitions utilized in the latter.

[7]The socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 in Afghanistan: Microsimulation of effects on multidimensional poverty, (OPHI, Oxford University and UNICEF in Afghanistan.

[8]Ibid.

[9]Ibid.

[10]World Bank, “Progress in the Face of Insecurity: Improving Health Outcomes in Afghanistan,” World Bank, Afghanistan, 13 (2018).

[11]Mashal et al., “Desperate for Any Coronavirus Care, Afghans Flock to Herbalist’s “Vaccine”,” New York Times, (June,2020).

[12]Tolo News, “Report Speaks of Corruption in MOPH,” Tolo News, (June, 2016).

[13]Pajhwok Afghan News, “Ventilators donated to MoPH smuggled to Pakistan,” (June,2020).

[14]نظیر داوی، “شیوع کرونا بقای نهاد های آموزشی خصوصی را با خطر رو به رو کرده است،” طلوع نیوز، (26 جون 2020).

[15]Joel Brinkley, “Money Pit: The Monstrous Failure of US Aid to Afghanistan,” World Affairs, vol. 175, 5: 13.

[16]Joel Brinkley, Money Pit, 18.

[17]Kate Clark, “The Cost of Support to Afghanistan: Considering inequality, poverty and lack of democracy through the ‘rentier state’ lens,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, Special Report (May, 2020).

[18]Mujib Mashal, “Afghanistan Needs Billions in Aid Even After a Peace Deal, World Bank Says,” New York Times (December, 2019).

[19]World Bank, “Financing Peace: Fiscal Challenges and Implications for a Post-settlement Afghanistan,” World Bank (December, 2019).

[20]Kate Clark, “The Cost of Support to Afghanistan,” (May, 2020).

[21]Guardian, “Maternal death rates in Afghanistan may be worse than previously thought,” (2017).

[22]The estimated rise in Afghanistan poverty levels from 54.5 to 72 percentage points is based on the World Bank Report, “Afghanistan Development Update July 2020: Surviving the Storm.” The can be accessed from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Afghanistan-Development-Update-Surviving-the-Storm.pdf

[23]World Bank, “Afghanistan Economic Update,” (April, 2012).