By Dr. David L. Luechauer

Some foreign observers claim that Gross National Happiness (GNH) provides ideological cover for repressive and racist policies. Love it or hate it, one thing is clear, the pursuit of Gross National Happiness does not appear to be helping the people of Bhutan rise to a higher standard of living.

Through self-promotion and with the assistance of some economists and progressive organizations the small nation-state of Bhutan has become the poster child for a metric of growth and sustainability different from the ubiquitous, Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

In contrast to GDP, which depends on money spent, regardless of what it is spent on, Gross National Happiness (GNH) attempts to quantify development in terms of the economy, the environment, and the culture of Bhutan. As a conceptual ideal, GNH seems to satisfy the requirements of sustainability.

In practice, GNH is difficult to define, measure, and implement. Bhutan is not nearly as far along the curve to embracing and enacting GNH as many promoters and Bhutanese politicos would have the world believe.

HIGHLIGHTS

HIGHLIGHTS

- Bhutan has maintained impressive economic growth and made commendable progress toward the Millennium Development Goals.

- Assessing the impact and effectiveness of GNH is difficult because Bhutan forbids immigration, and tourism is controlled under a strict regime to guard against corrupting influences. Travel within the country is tightly controlled and monitored: what foreigners see is well scripted and rehearsed.

- The biggest deprivations are in education, living standards and time use. Thus, even by their own measure of happiness, there is room for improvement.

- The country’s National Statistics Bureau revealed high acceptance levels of domestic violence. Around 70 percent of women felt they deserved to be beaten if they refused to have sex with their husbands, argued with them, or burned the dinner.

- When polled in class 92% of the 200+ graduating seniors in my class indicated a strong desire to leave the country indefinitely.

- It is increasingly evident that the vast majority of Bhutanese are only paying lip service to GNH as they vigorously pursue the goods, services, and lifestyle of their GDP measuring counterparts.

Introduction of Gross National Happiness

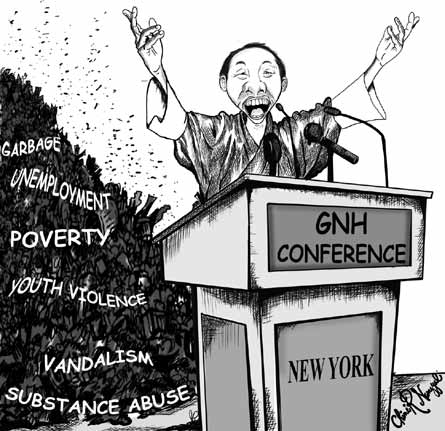

In August 2012 my family and I left the Royal Kingdom of Bhutan after a visit of eight months in which I served as a Professor at the Gaeddu College of Business studies. During our stay, Prime Minister Jigme Thinley and a number of Bhutanese officials were “parading” around the world eschewing the use of GDP and promoting Gross National Happiness (GNH) as a revolutionary new model of economic development and metric of national progress that all nations should embrace. Indeed, at Bhutan’s behest the UN held the first High Level Meeting on “Happiness and Well-Being: Defining a New Economic Paradigm” during the sixty-sixth session of the General Assembly. I found it both paradoxical and ironic that Bhutan was taking the lead in promoting such an initiative when the concept had yet to be fully actualized and conditions at home were so deplorable. Our observations and interactions with countless Bhutanese led me to conclude that the promise of GNH falls substantially short of the lived experience of the populace. Indeed, there was a lot more “hype” than happiness in GNH. Moreover, Bhutanese leaders were guilty of overpromising and under-delivering. The Bhutan Observer ran an editorial cartoon which captured the essence of that which we felt and experienced [see inset]. Likewise social media outlets such as facebook’s bhutantalk – a platform for constructive criticism; the highly controversial website http://bhutanomics.com which was banned by the government; and a new paper The Bhutanese have also emerged to shed light on the vast differences between that which Bhutanese leaders espouse and the day-to-day realities experienced by the populace.

The Promise of Gross National Happiness (GNH)

The concept of national happiness being supremely important has a long history in Bhutan, at least back to the legal code of 1729, which says “if the government cannot create happiness for its people, there is no purpose for the government to exist.” Gross National Happiness is much newer, dating to the early 1970s. Vexed by the Chinese invasion of neighboring Tibet and not wanting his country to suffer the same fate, the Fourth King of Bhutan Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, decided to modernize Bhutan and end its policy of isolation. He’d do this, however, in a slow deliberate way. The term “gross national happiness” [GNH] was coined in 1972. Ironically, the King first uttered it as an offhand remark as an indication of his commitment to building an economy that would serve Bhutan’s unique culture based on Buddhist spiritual values. Eventually, the concept was taken seriously enough that the Centre for Bhutan Studies, under the leadership of Karma Ura, developed a sophisticated survey instrument to measure the population’s general level of well-being. The goals of the national development process of Bhutan are primarily defined by three factors: 1] Peace, Security and Prosperity; 2] Achieving the goals of Gross National Happiness; and 3] Building a Vibrant Democracy all within the context of promoting and maintain the many unique aspects of Bhutanese culture. The nine domains and thirty three indicators of the GNH index are captured in the picture above. The first pre-pilot index was conducted in 2006, followed by a 2008 national survey, and then followed by the 2010 GNH Index.

The GNH Index is a multidimensional measure that is linked with a set program screening tools which guide policy implementation.

The GNH Index is a multidimensional measure that is linked with a set program screening tools which guide policy implementation. The GNH Index is a multidimensional measure that is linked with a set program screening tools which guide policy implementation.The GNH Index is built from data drawn from periodic surveys that are representative by district, gender, age, rural-urban residence, income, etc. Representative sampling allows its results to be decomposed at various sub-national levels. In the GNH Index “happiness” is multidimensional – not measured only by subjective well-being, and not focused narrowly on happiness that begins and ends with oneself. The pursuit of happiness is collective and different people can be happy in spite of their disparate circumstances. Measuring the extent to which people experience “sufficiency” in each of the 33 indicators of GNH is an important component of the overall calculation of happiness.

To date Bhutan’s leaders have adopted a very cautious approach to economic development, putting preservation of the traditional Buddhist culture and the country’s spectacular natural environment well ahead of ambitions for economic modernization. Since 1998 there have been successive years of robust growth with moderate inflation and a number of far-reaching structural reforms: the creation of a government department on telecommunications (access to foreign television and the internet was restored in 1999 after having been banned in 1990), the abolition of the state monopoly in petroleum distribution, the privatization of public enterprises in banking, trade, and cement manufacture as well as the creation of several joint ventures. In 2002, the government created the Bhutan Power Corporation (BPC) which is currently the largest corporation in the country. “Bhutan’s economy is growing and the government is committed to undertaking policy reforms to ensure that the growth is sustainable and will support provision of necessary services to its people,” said Juan Miranda, ADB’s Director General for the South Asia Department. Economic growth has averaged eight percent per year over 2001-2011 and Bhutan has steadily increased demand for consumer imports. Sales of hydropower – Bhutan’s main export – are expected to continue at current levels until 10 planned hydropower plants come on stream in the run up to 2020. Thus, Bhutan has maintained impressive economic growth and made commendable progress toward the Millennium Development Goals.

Bhutan has not yet been included in the Gallup World Poll on happiness, but has used the European Social Survey happiness question in its recent large (n=7,000) national survey. Bhutanese average happiness measured 6.05 on the 0 to 10 scale. This is lower than the 7.01 average in the latest ESS survey, but higher than in Russia, Ukraine and Bulgaria. Compared to Bhutan’s near neighbors, less precise calculations rank Bhutanese happiness levels slightly above those in India, and significantly above those in Nepal, China and Bangladesh.

King Wangchuck has said “Today’s world demands economic excellence and I have no doubt that during our lifetime we will be working towards building a stronger economy for Bhutan. In doing so, no matter what our immediate goals are, I am confident that the philosophy of GNH will ensure that ultimately our foremost priority will always be the happiness and the well-being of our people. In other words, I believe that GNH today is a bridge between the fundamental values of kindness, equality, and humanity and the necessary pursuit of economic growth.”

Realities of Gross National Happiness (GNH)

Assessing the impact and effectiveness of GNH is difficult because Bhutan forbids immigration, and tourism is controlled under a strict regime to guard against corrupting influences.

According to the Asian Development Bank, Bhutan is on the United Nation’s list of least developed countries (LDC) and the government has shown no particular eagerness to graduate from this status. Assessing the impact and effectiveness of GNH is difficult because Bhutan forbids immigration, and tourism is controlled under a strict regime to guard against corrupting influences. Travel within the country is tightly controlled and monitored: what foreigners see is well scripted and rehearsed. Moreover, the government reserves the right to block and ban speech – including websites – which it deems to be inflammatory or “anti-Bhutanese.”

I wrote a 2012 Kuensel editorial “GNH Begins At Home” which argued that the typical Bhutanese citizen does not enjoy even the most base level amenities, health/human/social services, products, protections, or freedoms of their counterparts living in GDP measuring nations. There are painfully few regulations on issues such as food storage/preparation or child safety/welfare. Pollution is increasing exponentially, there is no meaningful system of waste collection/disposal and bio-waste is mounting. Thus, I questioned why Bhutanese leaders were out promoting Bhutan’s GNH as an economic development model to follow when conditions in the country were so deplorable – dilapidated housing, unsanitary medical facilities, inability to procure healthcare. The outpouring of support from Bhutanese citizens was rewarding. I was not the only one to see that Bhutan did not live up to its self-created reputation as destination happiness.

According to the 2010 GNH index 10.4% of people were ‘unhappy’; 47.8% were ‘narrowly happy’; 32.6% were extensively happy’; and, 8.3% were ‘deeply happy’. Overall, the GNH Index indicated overall, 41% of Bhutanese are identified as happy. Only 59% enjoy sufficiency in 57% of the 33 domains. The index revealed that 49% of men were happy, while only 32% of women were happy. Women do better in living standards and ecology. Men do better in education, community vitality and psychological well-being. Men and women are about the same in health, time use, governance, and culture. Rural people are less happy than urban people. The 59% of Bhutanese who are not-yet-happy are more deprived in all 33 indicators than the happy people. The biggest deprivations are in education, living standards and time use. Thus, even by their own measure of happiness, there is room for improvement.

As noted in Bhutan’s 10th Five Year Plan, about one fourth of the country’s people—mostly from rural areas—continue to live below the poverty line. The report goes on to note that there are extensive gaps between rural and urban areas on income level, health care, and access to social services. A report by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) indicates that the shortage of skilled labor and technical expertise is chronic and severe. There is significant concern that 40 percent of the government’s budget is supplied by foreign grants or other aid packages and this number is rising rapidly. The ADB also reports that Bhutan is still challenged by a narrow economic base, low employment elasticity, inadequate involvement of the private sector in economic development, administrative limitations on the expansion of the private sector, and an extensive reliance on migrant Indian labor and expertise. Bhutan’s largest trading partner, India, provides 75 percent of Bhutan’s imports and takes 90 percent of its exports. Since this trade is conducted in Indian rupees, Bhutan is now suffering a severe shortage of the Indian currency. The rupee crunch, caused by the rapid buildup in public spending, poor liquidity management, and a lack of savings instruments, has instigated a significant slowdown in the growth of the economy and is producing a number of negative consequences. For the first time in recent history the Bhutanese unit of currency is not accepted by many Indian businesses and is patently worthless outside of Bhutan – we could not find a single exchange in Asia or USA willing to accept the Ngultrum.

Bhutan faces other challenges including accelerating levels of unemployment among youth and rural populations. Although exact rates have proven difficult to calculate, a 2013 editorial in the Bhutanese simply states, “the problem is spinning out of control.” Moreover, the typical youth would rather remain unemployed and await the creation of “white collar” civil services positions than seek employment in the private sector or a skilled labor position. The cost of providing public services such as healthcare and education is rapidly exceeding the nation’s ability to pay for them. Finally, Bhutan ranks extremely low on the World Bank’s ease of doing business index and even lower in the Heritage Foundation’s index of economic freedom.

Bhutan is not everyone’s idea of Shangri La. Earlier this year, the country’s National Statistics Bureau revealed high acceptance levels of domestic violence. Around 70 percent of women felt they deserved to be beaten if they refused to have sex with their husbands, argued with them, or burned the dinner. The country has also faced criticism for expelling residents it claims are illegal Nepali immigrants, but who some human rights groups assert were citizens opposed to the monarchy. In a 2011 study, which appears in the Journal of Multidisciplinary Health Care, a team of Bhutanese authors concluded that Bhutan is still a poor state, with 23.2 percent of the population living below the poverty line, and per capita consumption of US$24 per person per month. The socioeconomic disparity is evident: the richest 20 percent of the national population consumes 6.7 times more than the poorest 20 percent. There is also an increasing trend of mental disorders, with increasing numbers of young people suffering from stress and anxiety-related disorders. In fact, a study conducted by myself and colleague Umesh Jahav indicated that up to one third of the college population of Bhutan was already showing signs of alcoholism. Similar statistics for drug abuse were not far behind. Indeed, when polled in class 92% of the 200+ graduating seniors in my class indicated a strong desire to leave the country indefinitely. Tragically, less than 5% believed they would ever be afforded the opportunity to travel, study or live outside Bhutan.

Karma Phuntsho, a Bhutanese scholar of Buddhism at Cambridge University, laments the consumerism sweeping Bhutan: it is not uncommon, for example, to see flat-screen TVs in the many shacks and shanties that dot the landscape. People, he says, are becoming restless and materialistic. In Thimphu’s bars, young people are glued to Spanish football matches, prefer pop music to traditional or Bhutanese created music, play video games for hour upon hour, and dance to the latest hits from Western artists. Countless Facebook pages attest to the fact that they leap at every opportunity to wear Western style clothing instead of the legislated Gho and Kira. Most people carry mobile phones, yearn to own an automobile, and generally seek to emulate the behavior and lifestyle they see portrayed in the latest TV shows and movies imported from Hollywood, Bollywood and Korea. The shops are small, and full of low quality imported goods. Traffic lights will surely come. Bhutan it seems is becoming more like everywhere else instead of inspiring other nations or people to follow its lead. It is increasingly evident that the vast majority of Bhutanese are only paying lip service to GNH as they vigorously pursue the goods, services, and lifestyle of their GDP measuring counterparts.

In a rare moment of candor and humility, Prime Minister of Bhutan, Jigmi Y. Thinley, made clear in address to the United Nations, that “Bhutan is not a country that has attained GNH…. Like most developing nations, [it is] struggling with the challenge of fulfilling the basic needs of [its] people.” Moreover, in his address to the Gaeddu College of Business, His Majesty the 5th King stated: “Bhutan simply cannot afford to inherit or create ‘first world problems [e.g., violence, drug/alcohol addiction, social unrest, etc.] and attempt to solve them with third world resources.” Almost every indicator we saw and experienced in Bhutan suggested that it was heading in the direction of decay and decline rather than sustainable growth and development. Moreover, the typical Bhutanese neither appeared nor acted any more happy or content than the people of any other nation in which we visited or lived.

Conclusion

In 2011 the United Nations adopted a resolution that encouraged nations to “pursue the elaboration of additional measures that better capture the importance of the pursuit of happiness and well-being in development.” Since then, conferences focused on GNH have occurred in Canada, Thailand, the Netherlands, and Brazil. Several nations are conducting their own studies of GNH indicators and happiness surveys are being conducted in cities and regions worldwide. At present, there appears to be no shortage of politicians, economists, and social-commentators wishing to promote Bhutan as the new paradigm. Yet contrary to the way it is portrayed, Bhutan is not the last Shangri La. It is quickly losing its grasp on the values/practices which promote happiness. GNH is not a bandwagon upon which we should all be unquestionably jumping. As Simon Long notes in The Economist, “the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan is not in fact an idyll in a fairy tale. It is home to perhaps 900,000 people most of whom live in grinding poverty.” The headlines of the nations’ leading papers continue to document increasing levels of political corruption, the rapid spread of diseases such as Aids and tuberculosis, gang violence, abuses against women and ethnic minorities, shortages in food / medicine, and economic woes that make Bhutan barely discernible from any other nation. Given the size of its population, Bhutan is actually in much worse shape than most of the GDP measuring nations that GNH advocates like to condemn.

In the words of Dorji Penjor of the Centre for Bhutan Studies “even in Bhutan opinions differ about GNH. For its adherents, it offers a guide to policy that will enable Bhutan to pick and choose in the globalisation supermarket, modernising on its terms alone. Bhutan’s experiment, in this view, also offers important lessons to other poor countries. For critics, however, GNH is at best an empty slogan—one that risks “including everything and ending up meaning nothing.” At worst, some foreign observers claim that GNH provides ideological cover for repressive and racist policies.” Love it or hate it, one things is clear, the pursuit of GNH does not appear to be helping the people of Bhutan rise to a higher standard of living.

In my opinion, while the intent of GNH is laudable and the rhetoric is compelling, Bhutan is simply not the nation by which to measure either its efficacy or utility. Implementing and assessing new methods of economic development and models of sustainable growth will require political will, time, and a host of resources that Bhutan does not possess. While GNH may hold promise in countries better able to conceptualize, operationalize, measure, and critically evaluate its indicators, it is far too premature to suggest, let alone conclude, that Bhutan provides a model which any nation should follow. More importantly, my experience suggests that Bhutanese leaders and others interested in the well-being of the Bhutanese people would do greater service by addressing the vexing and pressing issues at home instead of trotting the globe espousing the virtues of GNH.

For Further Reading

A Short Guide To Gross National Happiness – http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Short-GNH-Index-edited.pdf

Beyond GDP – http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2010/06/gdp_versus_gnh.html

Bhutan’s ‘Gross National Happiness’ index – http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/ asia/bhutan/8355028/Bhutans-Gross-National-Happiness-index.html

Bhutan: The pursuit of happiness – http://www.economist.com/node/3445119

Dr. David’s critique of Bhutan’s GNH story – http://www.ipajournal.com/2012/09/23/dr-davids-critique-of-bhutans-gnh-story/

Frontline: Gross National Happiness – http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/bhutan/gnh.html

Gross National Happiness – https://sites.google.com/site/wintobates/Home/gross-national-happiness

Gross National Happiness – http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/

Health and GNH – www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=10698

Luechauer GNH Begins From Home – http://www.bhutannewsservice.com/column-opinion/commentry/gns-begins-from-home/

Measuring GNH – http://www.un.int/wcm/content/site/bhutan/cache/offonce/pid/7869

What Is GNH – http://www.gnhbhutan.org/about/

World Happiness Report – http://www.earth.columbia.edu/sitefiles/file/Sachs%20Writing/ 2012/World%20 Happiness%20 Report.pdf

(David L. Luechauer, PhD, is a visiting Professor at Krannert School of Management Purdue University. The views expressed in this article are his own and do not necessarily represent the views of Global South Development Magazine or Silcreation Finland)

[…] L. Luechauer in an online article entitled The False Promises of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (Global South Development Magazine), “the typical Bhutanese citizen does not enjoy even the […]

GNH can be seen and judged from two angles, one that’s disgruntled would obviously have narrow and unconstructive criticisms. While the rest would thank the fact-that Bhutan is promulgating the idea of GNH to rest of the world.

Mr. Luechauer already expressed his critical views in the Bhutanese media and he was free to do it, even as a foreigner. Then I responded agreeing with some of his observations, finding some of his analysis superficial, but what I really missed was his feasible solutions. I missed his well-intended proposals. I could not see his good intention and his empathy to wholeheartedly try to help Bhutan. A small nation in transition struggling with all the global forces beyond their control.

My other point was this: there is no perfect or even near to perfect democracy and free market economy in any country in the world, including the USA. Still, they are great inspiring ideas and many people go around the globe promoting them – politicians and ordinary citizens like Mr. Luechauer. If they have the rights to do so, why not to give the same right to Bhutan to promote the GNH concept? Only big and powerful cultures have the right to promote their ideas?

I think we are in the same boat – on the same planet – and we need more constructive and innovative solutions to re-organise our economies now, so that together we can create a better world for all. And GNH at least promises to provide a new perspective which I believe is worth contemplating.

You can read my full response to him here:

http://www.thebhutanese.bt/gnh-american-dream-and-real-life-part-1/

http://www.thebhutanese.bt/gnh-american-dream-and-real-life-part-2/

Zoltan

Mr. Luechauer already expressed his critical views in the Bhutanese media and he was free to do it, even as a foreigner. Then I responded agreeing with some of his observations, finding some of his analysis superficial, but what I really missed was his feasible solutions. I missed his well-intended proposals. I could not see his good intention and his empathy to wholeheartedly try to help Bhutan. A small nation in transition struggling with all the global forces beyond their control.

My other point was this: there is no perfect or even near to perfect democracy and free market economy in any country in the world, including the USA. Still, they are great inspiring ideas and many people go around the globe promoting them – politicians and ordinary citizens like Mr. Luechauer. If they have the rights to do so, why not to give the same right to Bhutan to promote the GNH concept? Only big and powerful cultures have the right to promote their ideas?

I think we are in the same boat – on the same planet – and we need more constructive and innovative solutions to re-organise our economies now, so that together we can create a better world for all. And GNH at least promises to provide a new perspective which I believe is worth contemplating.

You can read my full response to him here:

http://www.thebhutanese.bt/gnh-american-dream-and-real-life-part-1/

http://www.thebhutanese.bt/gnh-american-dream-and-real-life-part-2/

Zoltan

[…] There are mixed reviews about Bhutan’s GNH. For more information, check out Gross National Happiness.com. For a more critical analysis, check out The False Promises of Bhutans GNH. […]

While I agree with Dr. David on the gist of the article that there are more things to do at home then promoting GNH to the world. However, on the other hand, a policy tool and development policy I see no harm in having ” sustainable and equitable socio economic development, environment conservation, good governance and preservation of culture.” I am positive that they are a ver good set of indicators, added with other indicators which makes it a great deal. As for not allowing tourists to do what they want and how, you go it totally wrong man~ I have had tens of my friends from US, Canada and Europe come as tourists and guests, who roamed the country free and wild.. some even on cycles or bus rides.. Perhaps you were too worried about Lhatu Jamba that you didnt leave Gedu on your own…

Also, I do agree that Bhutan might not be the best country to advocate GNH to the world. But you name one country that does not have a problem? US/Sweden/Norway/China/India… My perception is that all nations have problems..And one has to start.. Bhutan is going to bell the cat..You guys run away.. or you suggest us something..

As for willingness to immigrate. I am not sure about your poll.. But you that with a US university as well.. Every young mind in the world wants to travel abroad and explore..perhaps your question was misleading on immigrating vs travel abroad.. Unless you want leaders like Bush who had hardly travelled before bcoming a president.. Most Bhutanese – 90% of civil servants would have atleast travelled to 2-3 countries and have a good global/multi-cultural perspective. Gedu students might have been wanting to explore.

Indeed! a narrow-minded, if not callous, account of a disgruntled expat no more in Bhutan. In a perfect world, there wouldn’t be a need for GNH. Utterly naive of the author to compare Bhutan, a developing nation, with standards of the developed world. Remember, Bhutanese are people too! You have only yourself to blame for romanticizing Bhutan.

Thanks for this insight. Gives an account of the practice as different from policy