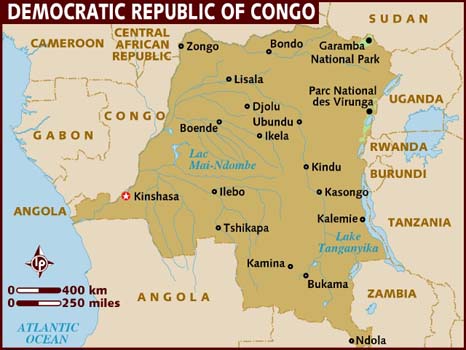

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is not officially at war, but for decades the ordinary Congolese haven’t experienced an essence of peace either. After years of bloodshed and devastation, the DRC is staggering towards normalcy, but after brief intervals the country finds itself rebound into violent conflicts again and again. This Spring 2012 edition of Global South Development Magazine tries to analyse some of the issues that have been responsible for prolonging conflict and unrest in the DRC. This is the first section and it gives a historical timeline of the DRC followed by an account of our DRC correspondent from the field. This edition’s interview section and the editor’s column have been dedicated to the DRC issue as well.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is not officially at war, but for decades the ordinary Congolese haven’t experienced an essence of peace either. After years of bloodshed and devastation, the DRC is staggering towards normalcy, but after brief intervals the country finds itself rebound into violent conflicts again and again. This Spring 2012 edition of Global South Development Magazine tries to analyse some of the issues that have been responsible for prolonging conflict and unrest in the DRC. This is the first section and it gives a historical timeline of the DRC followed by an account of our DRC correspondent from the field. This edition’s interview section and the editor’s column have been dedicated to the DRC issue as well.

The DRC: A Historical Timeline

Congo gained independence from Belgium in 1960 but immediately fell into a state of chaos and disintegration. In 1965, Colonel Joseph Mobutu seized power through a coup quietly approved by the Western powers, and changed the country’s name to Zaire and his own to Mobutu Sese Seko. Zaire became an important pawn in the Cold War as an African bastion of anti-communism. This helped Mobutu to hold his gigantic and ethnically divided country together. When rebel movements threatened to overtake parts of the country in 1964 and in 1977–78, Western powers intervened with military support. Even during the last months of Mobutu’s reign in 1997, France allegedly organized the hiring of foreign mercenaries in order to avoid the dictator’s fall from power.

In the 1970s, Mobutu and his cronies seriously started to lay their hands on the country’s wealth. In a process called ‘Zairianization’, key economic sectors were put under direct state control Mobutu’s kleptocratic regime was coupled with poor growth rates and a mounting public external debt. International donor pressure and the end of the Cold War finally forced Mobutu to abandon one-party rule in 1990. He also became more marginalized as the government in Kinshasa assumed some of his former powers. But Mobutu would make an unexpected comeback on the world scene.

The Rwanda Genocide and the War Against Mobutu: 1994–97

To understand the insurgency against Mobutu in 1996, it is necessary to recount earlier developments in neighboring Rwanda. Rwanda’s two major ethnic groups, the Hutu and the Tutsi, had fought a small-scale civil war since 1990 when an army of Tutsi rebels (RPA), hosted and supported by Uganda, invaded the country. The dramatic turning point happened in 1994 when Rwanda’s Hutu president Habyarimana was killed along with Burundi’s president after their plane was shot down. Although it is still not clear who was responsible for this attack, extremist Hutu groups drew their own conclusions and soon started a systematic genocide of the civilian Tutsi minority in Rwanda. According to some estimates, around 800,000 people were killed in a few months.

The RPA and its leader Major Colonel Paul Kagame managed to conquer Kigali and oust the Hutu government. Fearing Tutsi revenge, around 1.2 million Hutu, including some 40,000 of the militia responsible for the genocide, fled to the North and South Kivu provinces in neighboring Zaire. At this point, Mobutu saw an opportunity to regain the initiative. He agreed to host the refugees on Congolese soil and thereby became a partner to international aid organizations. The move also allowed him to regain some respectability, at least in the eyes of the French, who once again embraced him.

At the same time, Mobutu used the inflow of Hutu to instigate hostilities towards the Banyamulenge, a people of Tutsi origin who had lived in eastern Congo for generations. The parliament even decided that the Banyamulenge should lose their citizenship. In October 1996, the governor of South Kivu ordered the Banyamulenge to leave their homes within a few days. In desperation, they turned to their Tutsi cousins in Rwanda for help.

The new rulers in Rwanda had an even greater grievance on their hands. The Hutu militia used the refugee camps in Kivu as a base for attacks against the Tutsi-dominated regime in Rwanda. Helped by Mobutu, they became a serious threat to the new government’s security. In September 1996, the RPA joined the Banyamulenge and attacked the Hutu refugee camps on Congolese soil.

They were soon joined by several anti-Mobutu rebel groups and engaged in battles against government forces. Among the groups that joined the rebellion was a small one called PRP led by Laurent Kabila. Kabila belonged to Lumumba’s socialist faction in the 1960s, but after Mobutu’s consolidation of power, Kabila and his men withdrew to the South Kivu mountains where they formed something of a mini-state. Not much is known of his activities from then on, except that during long periods he made a living as a gold smuggler.

From late 1996 he suddenly appeared as the leader of the newly formed Alliance of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (ADFL). It was therefore suspected that Kabila was something of a puppet, at least initially – suspicions that were later confirmed in interviews with Rwanda’s strongman Paul Kagame. The ADFL and their Tutsi comrades immediately remarkably successful. Mobutu’s unpaid army, which he had kept weak and divided so that it would not pose a threat to himself, melted away as the Tutsi veterans approached. During their march westwards, some 200,000 Hutu refugees were allegedly killed, and conquered mines were looted.

The old Cold War allies Belgium and the United States declared that they would no longer come to Mobutu’s rescue. Only France, frightened by the prospect of an English-speaking new regime, remained Mobutu’s friend to the bitter end. On 17 May 1997, Kinshasa surrendered to Kabila’s troops and the old dictator fled the country.

The Great African War: 1998

Early in his presidency, Kabila showed signs of moving towards one-man rule. His control over state resources was highly personalized, and public enterprises were not managed in any long-term sense of the word but rather used to rapidly generate finances through indiscriminate concession granting Corruption, patronage, and lack of accountability came to characterize Kabila’s presidency, rather than the hoped for democracy and national development.

Kabila’s alliance with Rwanda and Uganda was strong immediately following his rise to power. His government contained many Tutsi (both Rwandan and Congolese) and Banyamulenge in top political and military positions.This placed a strain on Kabila’s legitimacy, as most Congolese regarded them as foreign occupiers, which in turn led Kabila to marginalize the Tutsi and Banyamulenge members of his administration. A more plausible explanation for this action could be that Kabila, perhaps inspired by the actions of Mobutu before him,was desirous of keeping the financial gain from Congo’s resources for himself. Whatever the explanation, Kabila dismissed a Rwandan military officer of Tutsi ethnicity as chief of staff for the Congolese armed forces in July 1998. He then went one step further, sending the commander and his Tutsi Rwandan comrades-in arms back to Rwanda on 27 July 1998. This move was an apparent attempt to pre-empt a coup, and was a direct cause of the rebellions that took place in both Goma and Kinshasa six days later.

After the failure of these rebellions, troops from Rwanda and Uganda entered Congo in August 1998. Both countries stated security reasons for the deployment. The crisis escalated when Rwandan troops, with some support from Uganda, attempted to seize Kinshasa. At this point, Zimbabwe and Angola intervened on behalf of the Kabila government, saving it from collapse. Namibia, Chad, and Sudan would later join Kabila’s allies, although Chad and Sudan withdrew relatively early.

Angola entered the war in Congo primarily for security reasons; UNITA rebels had been using Congo to launch attacks on Angola. Namibia had no immediate security concerns, but rather supported Kabila based on a decision by President Nujoma, which was mostly symbolic in nature. Zimbabwe does not share a border with Congo, and did not face any security threats. The reasons for its involvement seem to be related to investments made in Congo by the government and Zimbabwean businesses.

Economic gain appears to have been a powerful motivator in this war, and there isageneralconsensusthatRwanda’sand Uganda’s armies quickly began to shift their attention to commercial enterprise and exploitation. The gains from these activities were used to enrich the governments involved, finance the continuation of the war, and pay individual soldiers.

The plunder of Congo’s natural resources took place in two phases. The first involved the wholesale looting of existing stockpiles and took place in the occupied regions of Congo during the first year of the second war. The second phase involved systematic extraction and export of natural resources. This phase involved both foreign and Congolese actors. Both phases were greatly facilitated by the strong transportation networks put in place during the first war.

Economic data collected by the UN illustrate the trends in mineral exports in Uganda and Rwanda for the years 1994 to 2000 and the trends in mineral production in Rwanda for the years 1995 to 2000. Uganda had no reported coltan or niobium production after 1995, while exports increased steadily between 1997 and 1999. Finally, neither Uganda nor Rwanda has any known diamond production.

In the case of Zimbabwe, however, there is evidence of extensive commercial activity in the form of joint ventures and mining concessions. Natural resource extraction, particularly mineral extraction, fuelled the continuation of the conflict in Congo.

Rwanda’s military benefited directly from the war in various ways. The most significant of these has been the extraction of coltan, the price of which rose phenomenally between late 1999 and late 2000. The UN estimates that the Rwandan military could have been selling coltan for as much as $20 million per month.This allowed Rwanda to continue its presence in Congo, protecting individuals and companies who provided minerals. In some cases, the Rwandan army went so far as to attack rebel groups in order to appropriate their coltan supplies. While the Ugandan government was not directly involved in the extraction of natural resources, it did not take action against military and businessmen who participated in this activity. However, several events have improved the chances of ending the conflict in Congo. The first is Joseph Kabila’s rise to power after the assassination of his father in early 2001.The younger Kabila seems to have shown interest in finding a solution to the conflict and reinstating democracy in Congo. Agreements focusing on the transition of the Congolese government towards democracy have been signed, and foreign troops have withdrawn from Congolese soil. However, optimism must be tempered given the persistent fighting between rebel groups in the northeastern part of Congo. This has led the UN to adopt Resolution 1493, which authorizes the deployment of UN peacekeepers. (Timeline text source: Congo: The Prize of Predation by Ola Olsson & Heather Congdon Forse)

This article originally featured in the April 2012 issue of Global South Development Magazine along with a DRC Country profile and Emily Lynch’s excellent article reflecting on her time on the ground in the Congo. You can download the issue in its entirety for free.

[…] The Democratic Republic of Congo: A Historical Timeline […]

[…] Diary: A Reflection From The Field. « Previous / Next » By thedevelopmentroast / June 6, 2012 / Africa, Congo, Economy, Environment, […]