Generic drugs made in India are saving lives around the world. But if the country’s Supreme Court rules in favour of Big Pharma, all that could change, says Simon Reid-Henry.

The Indian Supreme Court opens today for the concluding stage of a long-running assault on India’s patent law by drug giant Novartis.

For six years Novartis has been trying to get Indians to pay market price for one of its patented drugs, Glivec – a life-saving anti-cancer medicine. Like other Big Pharma, Novartis believes that middle-income countries such as India and Brazil are no longer dirt poor and should now be paying their way for medicines. It argues that India should button up and follow the 40 other countries that already recognize the patent on Glivec.

But this is rather like saying it thinks India should jump under a bus on the grounds that others have been coaxed into doing so, and it sidesteps what is really at stake in today’s case. Because while India is a lucrative market and Glivec a blockbuster drug – with a price tag of around 10 times the generic equivalent – the tenacity with which Novartis has clawed its way through the Indian legal system to bring its case before the Supreme Court belies a far more significant pay off.

India now exports as much as 50 per cent of its $15 billion generics industry to other countries and supplies many of the medicines used in global health treatment programmes around the world

By challenging not only the rejection of its own patent, but the constitutional legality of a key part of India’s patent law, Novartis has in effect teed up an important litmus test of the sorts of flexibilities that emerging economies can draw upon to protect their own domestic industries under governing WTO TRIPS (trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights) legislation.

This means that if Novartis ultimately win the case, they not only open up the potentially lucrative Indian market for their own drugs, they will also force all Indian pharmaceutical producers to think twice about the sorts of drugs they make cheap versions of in future. And by further pegging India to rich-country levels of patent protection, the ultimate consequence may be to undermine the country’s entire generics revolution.

An Indian lifeline

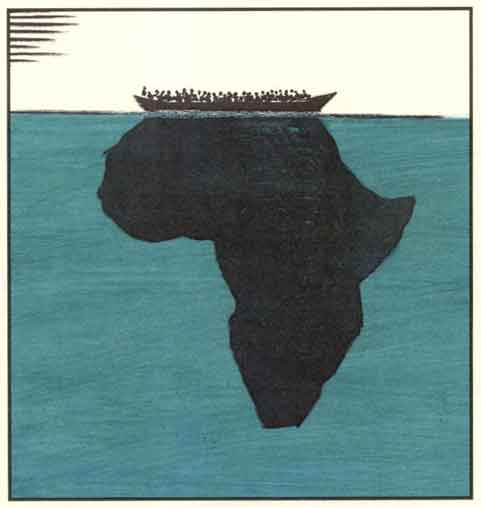

The implications of this reach far beyond India’s borders. For while it is well known that India produces cheap generic drugs, it is less well known that India now exports as much as 50 per cent of its $15 billion generics industry to other countries, or that Indian generics supply many of the medicines used in global health treatment programmes around the world. The medical group Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF) source 80 per cent of the HIV drugs that they use across the developing world from India, for example. Which makes India, as MSF spokesperson Leena Menghaney puts it, ‘literally the lifeline of patients in the developing world’.

But that lifeline itself is protected by the very part of India’s patent law that Novartis seeks to challenge. Section 3d, as it is known, was a public health safeguard that India adopted when it became officially TRIPS compliant in 2005. It is specifically intended to prevent what Novartis have for years been trying to do with Glivec: namely to extend the life of an older patent through clinically insignificant modifications, a practice known as ‘ever-greening’.

This case will – by luck or by design – undermine the legal room for maneouvre that India’s generics revolution relies upon

Novartis strongly reject this. They say that activist groups like MSF, ‘are confusing the issue’ by claiming that the case will affect generic medicines produced in India for the developing world. It is hard to feel all that sympathetic for Novartis, here. India has only become the pharmacy of the developing world because until now it has been so easy for them to undercut Big Pharma’s preference for a vastly overpriced market. And proven unwilling to compete on price, Novartis’ current actions now further paint them in the well-slippered guise of the monopoly capitalist, banging their fists on the table and crying foul play while doing all they can at the same time to rewrite the rules in their favour: they must surely know that by cranking up the risks for Indian generic producers this case will – by luck or by design – undermine the legal room for maneouvre that India’s generics revolution relies upon.

Regardless of the outcome, the world should follow what happens in New Delhi from today with interest. Novartis’ backdoor attempt to lob the hand grenade of Western monopoly rights into India’s well-functioning generics laboratories is likely to be just one of many coming salvos in the battle to meet, and to profit from, the health needs of those parts of the developing world with a dollar or two in their back pocket. Expect the EU-India Free Trade Agreement to be the next to try. And expect many people’s health to suffer if either attempt is successful.