By Robin Smith

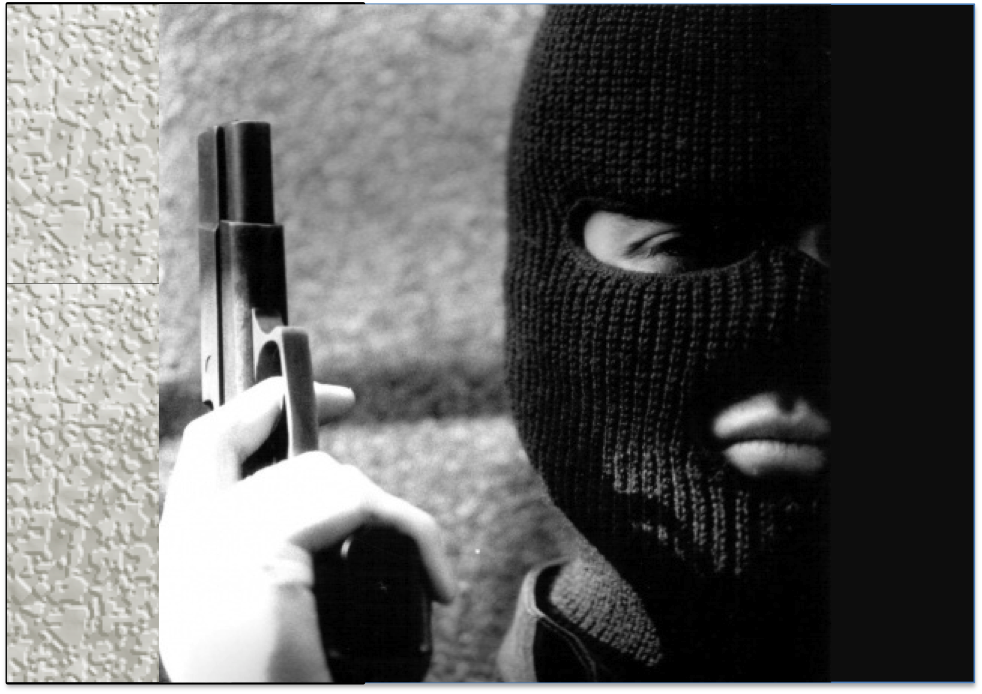

Vigilantes. Patrulleros. Los Encapuchados. Civic groups. By any name, civilian security groups are growing more common in Guatemala and their presence more controversial. To some Guatemalans, the vigilantes are their only hope in this failed security state where towns are increasingly targeted by gangs and drug traffickers who have relative immunity thanks to an untrained, understaffed and corrupt police force. Yet, for the targets of their violence, the night patrollers are no more than masked thugs. In my own two and a half years in Guatemala, I have struggled with conflicting feelings toward these groups as being both a necessary evil and an uncontrolled and dangerous element in a country on the verge of becoming a failed narco-state.

So who are the patrulleros?

The men who walk the streets after 11pm are usually attempting to end home invasion, petty crime, and drug deals in their neighborhoods. These groups often form after major national disasters, such as Hurricane Stan in 2005 and Hurricane Agatha in 2010 when thieves take advantage of evacuated neighborhoods and over-burdened municipalities who are struggling with the effects of flooding, landslides and infrastructural failures. Civic groups form to help rebuild and protect devastated areas. But the reason that these groups continue might be that “normal” life in Guatemala is like a game of Russian roulette – danger underlies daily life and the next bus trip could very well be the bullet that ends it all.

Guatemala has the highest crime rate in Central America, the fallout of the 36-year civil war and genocide that ended in 1996. Cities are over-run with gangs who perpetrate bus hijackings and bombings, shootings, kidnapping, rape, and terrorist tactics involving dismembering of adolescents and infants. The US State Department reports that Guatemala averages 42 murders per week, yet the prosecution rate is between 2 and 3%. In addition, the Mexican drug cartel, the Zetas, have begun to infiltrate the northern highlands, which led to a massacre of farm workers in May 2011. And though the incoming President, ex-military General Otto Pérez Molina, has promised to rule with a “Mano Dura”, an iron fist, his political connections and actions during the civil war are highly suspect. The best he is offering is an ominous militant regime.

So with statistics like this, who wouldn’t want to take crime policing and punishment into their own hands?

The first local vigilante action I became aware of in the province of Sololá in Guatemala’s Western Highlands was in December of 2009, when a public “chicken” bus was hijacked en route from Sololá city into the nearby tourist town of Panajachel. The driver was shot in the head and a passenger who tried to save the bus from plummeting off the mountain was also killed. When the three extortionists were finally apprehended, the townspeople gathered in front of the police building and demanded they be handed over to the public for punishment, as per the presumed rights under the Maya Code. When denied their demand, the mob rioted, burning police cars and the police station, until the thieves were handed over and lynched in front of the municipal building.

See Also: Honduras: Violence, repression and impunity capital of the world

Two weeks later, another lynching occurred in Panajachel. A man and three women were caught stealing at the town market. The police apprehended the women, but the male was caught by the villagers, brutally beaten, dragged behind a tuk-tuk (a rickshaw taxi), and set on fire in front of the police station. A drunken mob of Panajachel and Sololá residents called for the release of the other thieves, including a woman who said she was eight months pregnant. The entire event was being broadcast, play-by-play, on the radio as the rioters burned police vehicles. The police retaliated with tear gas and relocated the prisoners to a more secure location via helicopter.

It was the first lynching in Panajachel, and it scared many locals, but others insisted that it was necessary because otherwise the town would be bullied by gangs like the rest of Guatemala. Yet the extreme violence made me wonder: was this type of retaliation really necessary?

Five months later, in May of 2010, Guatemala was slammed with Hurricane Agatha. Flooding and mudslides left many people homeless and injured and 160 dead. More than 180 roads were destroyed and 161 bridges as well as water and electric infrastructure. As roads were impassible, it was difficult for towns to bring in food and other necessities. Though international aid money was coming in, the villages were not receiving any help, and the re-birth of the civic groups began.

At first I was impressed by the sense of community that was growing out of this disaster. However, as the weeks passed, the civic group wasn’t just asking neighbors for money to rebuild, but also for walkie-talkies, cell-phones, and nightsticks to carry during their nightly patrols. In September of 2010, 50 representatives of the neighborhoods received permission by the local government to form security groups consisting of a total of 1,200 members. The agreement stipulated that members would register with the municipality and the police would collaborate by responding to their calls, respecting their eye-witness testimony, and ensure prisoners were not released without processing through the court system. The groups did not have permission, though to shoot, kill, or severely injure anyone.

All that began to change when some of the groups started wearing masks, supposedly for their own protection, earning them the name los encapuchados, meaning “the hooded”. Then a local strip club was burned to the ground and the owner was beaten and left for dead in the river by a large group of vigilantes. They claimed to have found illegal arms in the owner’s home, as well as many other stolen goods, and said he was a menace to society. Suddenly, “social cleansing” was the phrase being thrown around in the editorial columns of newspapers.

Rumors spread that new groups were forming in opposition to the original ones in a mini-vigilante war. Then the Evangelicals joined the act, supporting punishment of anyone doing anything “immoral”. A masked vigilante raped a young woman on her way home from a bar, an incident that was captured on the security camera of a local hotel. A local man was beaten and forced to drink water from the sewer pipe. Two more men were followed and beaten for being out after 11 and for the “crime” of being intoxicated. Our “protection” began to look a lot like gangs.

Then, on October 8, 2011 23-year-old Luis Gilberto Tian Sente disappeared. As reported in the national news (The Prensa Libre 26 Oct. 2011 Edition, page 18), as well as by witnesses that night, Luis was with two of his friends walking home from the town yearly festival when 20 masked vigilantes captured him. Luis had been drinking, which may be a reason he caught the eye of the group, though the real reasons he was targeted are unclear. The mother of his two children posted flyers for information of his whereabouts, but the only trace of Luis were his bloody clothes found in one of the local soccer fields. Shortly after his disappearance, several journalists of the Panajachel community publicly accused three encapuchados, by name, of his murder in local and national newspapers, on the radio, and on the web. What the public did not know was that one journalist had access to a phone call that Luis made at the time of his capture and was able to identify, by name, four of the members of the registered civic group, including the President and Vice-President of the group. The journalists received death threats and left Panajachel for their own safety, but the two senior encapuchados were finally apprehended and imprisoned. The other two remain at large and the investigation does not appear to still be active. Currently a petition is being passed around for the release of the perpetrators as they have a lot of influence in the town.

So what to make of all of this? I met with local Guatemalans for their views on the vigilantes. The overwhelming consensus was that they are an improvement in town security, except for the encapuchados: It is generally agreed that the masks and anonymity afforded by them lead to an abuse of power. One Pana resident named Miguel said that he supported the vigilantes because people shouldn’t be out drinking and that the groups were just “cleaning up” the town. A former military member, and now bank security officer, said that the groups were the only reason his neighborhood is now safe from drug dealers who were plaguing the area and that his wife could now walk home alone at night.

The most interesting comments I received were from a local named Chico. When I asked him if the town was safer now or before these groups were formed, he said, “That is a question only a gringo (foreigner) would ask. For us, this way of life, the violence, the corruption, has always been there. We have never known anything else. To you, where you are from, maybe all of this looks different, but here this is normal. It is all the same.”

When commenting on the people who had to leave town for speaking out about alleged perpetrators of Luis’ disappearance, he said, “Why did they talk without proof? If I hear rumors, I don’t say them unless I have real evidence, video, pictures, something. They put themselves in danger by what they did. That can’t be blamed just on the vigilantes. Here, you don’t say anything unless you can prove it.” His words are eerily reminiscent of wartime in Guatemala.

So, when there is no witness protection, the police can’t be trusted, and even the government has blood on its hands, is there an option besides civic action? Guatemala is on the brink of becoming another Columbia or Mexico, where military policing, guerrilla groups, and civilians have to battle it out for control. It is a battle without winners and where the average citizen is the one who suffers most. And I wonder, is there time for Guatemala to save itself?

Latest Update:

Recently, Panajachel has seen a drop in the number of civic groups. The municipality has said that patrolling members should not be masked, though there have been sightings of encapuchados still.

Note: Historically, In the 16th century, the shore of the lake in Panajachel was the scene of a battle in which the Spanish and their Kaqchikel allies defeated the Tz’utujils. It was during the period of the Spanish conquest of Guatemala. The town attracted many hippies in the 1960s, but the numbers of foreign visitors plummeted during the Guatemalan Civil War.

This article appeared in the January 2012 edition of Global South Development Magazine, focused on Failed States. You can download it for free here.

My opinion, and I was announced by a Manta. Check your facts first if you want to change the world.

[…] Los Vigilantes in Guatemala: When State Security Fails […]

[…] Los Vigilantes in Guatemala: When State Security Fails […]

[…] Los Vigilantes in Guatemala: When State Security Fails […]

[…] Los Vigilantes in Guatemala: When State Security Fails […]