Pakistan and India has been locked in mutual enmity from the very day both got independence from their English colonizers in 1947. Both countries have fought three formal wars and many informal military skirmishes mostly won by India. Yet the realities of globalization and the criticality of trade for development has seen peace talks between Pakistan and India going on and off for the last fifteen years.

The United States played a major role in convincing India to resume the dialogue process. However, two steps forward and three  steps back has been the sum of progress to date. The biggest jolt for the peace process between the traditional rivals in south Asia was the November 2008 terrorist attack in Mumbai that prompted India to withdraw from all talks unless Islamabad round the alleged terrorists operating from Pakistan. The United States played a major role in convincing India to resume the dialogue process despite little progress on Indian demands for retribution.

steps back has been the sum of progress to date. The biggest jolt for the peace process between the traditional rivals in south Asia was the November 2008 terrorist attack in Mumbai that prompted India to withdraw from all talks unless Islamabad round the alleged terrorists operating from Pakistan. The United States played a major role in convincing India to resume the dialogue process despite little progress on Indian demands for retribution.

See Also:

- Who will win the Power Struggle for Tajikistan in the Central Asian ‘Great Game’?

- Can War Be Good for Development?

So when Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and his Pakistani counterpart Yusuf Raza Gilani joined each other in early April 2011 to watch the Pakistan-India cricket semi-final in the town of Mohali, it was a welcome resumption auguring well for all the countries across south Asia. South Asian reality fashions itself around the might state of India wherein only Pakistan has been the stumbling block frustrating regional efforts for greater citizen interaction and multilateral trade under the aegis of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).

The resumed dialogue process discussed a Pakistani appeal that India drop its opposition to an EU duty waiver on Pakistani textiles exports. It was exciting that improved trade ties could be a game-changer in regional politics, trade and economics. Pakistan had earlier resisted improving trade without first settling the Kashmir dispute. By early November, New Delhi agreed to the EU duty waiver and, more significantly, Pakistan granted the coveted Most Favoured Nation (MFN) status to India.

However, local politics in Pakistan evolved in a way that went on to change that mood. Reports have surfaced in the Pakistani media that the army had reservations about granting MFN status to India. The Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD), the humanitarian wing of the banned Lashkar-e-Taiba militant group blamed for the Mumbai massacre launched protests against granting India MFN status, saying that the Kashmir dispute must be settled first.

Shortly after the NATO airstrikes on a Pakistan’s army posts on the Afghan border killing 24 soldiers and wounding another 15, the JuD protest to mourn the soldiers killed turned into a protest against improved trade ties with India. This also synchronized with the breakdown of civil-military relations in Pakistan.

The civilian government has been adamant in pushing ahead with its agenda of peaceful cooperation with India. Recently, Pakistan’s Interior Minister Rahman Malik announced the intent to sign a liberal visa regime with his counterpart on his planned visit later this month. However, the civilian government has been on a very tight military leash and the signs of a consensus for rapproachment with India hardly look good. Progress in relations with India has become – quite unexpectedly – one of the few sensitive valves available to the civilian government to ease off the pressures building up against President Zardari’s government in Pakistan.

The civilian government has been adamant in pushing ahead with its agenda of peaceful cooperation with India. Recently, Pakistan’s Interior Minister Rahman Malik announced the intent to sign a liberal visa regime with his counterpart on his planned visit later this month. However, the civilian government has been on a very tight military leash and the signs of a consensus for rapproachment with India hardly look good. Progress in relations with India has become – quite unexpectedly – one of the few sensitive valves available to the civilian government to ease off the pressures building up against President Zardari’s government in Pakistan.

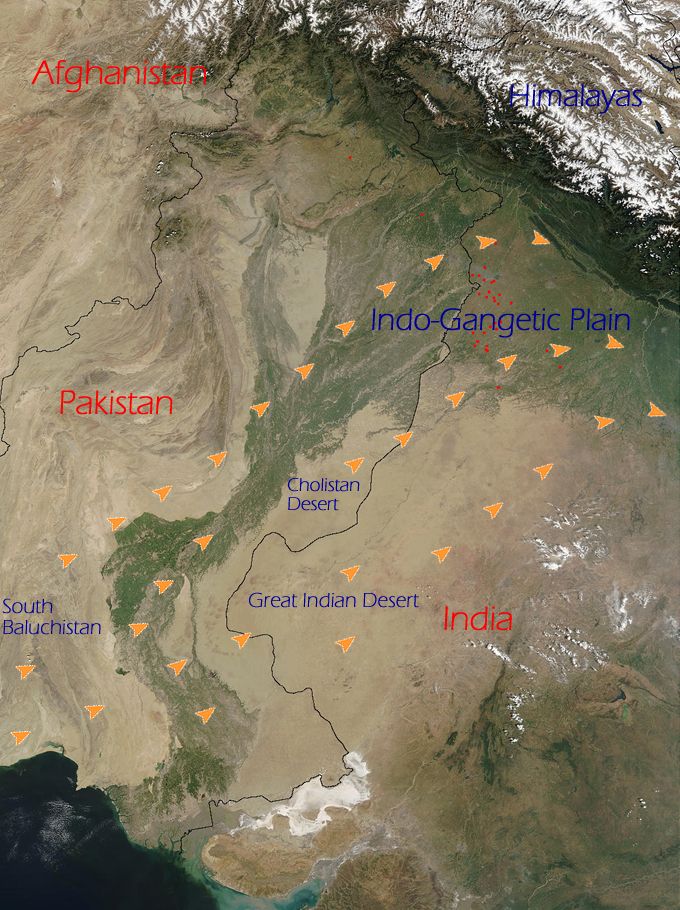

This is not very surprising given the sharp escalation of US rhetoric as Pakistan defiantly refused to take any action against the so-called Haqqani group of the Taliban. The group has been described as a ‘veritable fighting arm’ of the Pakistani spy agency ISI by a top US general, and has been held responsible for the several terrorist attacks on US and its allies in Afghanistan. Pakistan army, however, considers acting against the Haqqani group against national interests that involves reviving its influence in Afghanistan after the US withdrawal. This has been a part of Pakistan’s ‘strategic depth’ strategy aimed at countering Indian hegemony in the region.

The Pakistani Ministry of Foreign Affairs last month summoned the country’s ambassadors from a number of leading countries – the U.S., EU, Russia, Afghanistan and India– for a meeting at home. The meeting is linked with an upcoming revision of Pakistan’s foreign policy doctrine that has markedly changed since the NATO air strikes. Despite the American and NATO military domination in Afghanistan, it is no longer up to them to decide how and when to end the longest ongoing war in modern history. And the main reasons are not the fierce Taliban or a terrorist Al-Qaida but the long-standing antagonism between India and Pakistan.

“Pakistan does not want Afghanistan to become a satellite of India”, Clinton said last year, “so it has in the past invested in a certain amount of instability in Afghanistan”. Her reference is to the Pashtun Taliban in Northern Waziristan that has been fighting the coalition forces in Afghanistan besides bleeding the Indian economy and tying up her army in Kashmir, the region over which it has a running conflict with Pakistan since 1948. Pakistan’s support to these Taliban also translates into a traditional antagonism with the Tajiks and Uzbeks in Afghanistan who have been historically hostile towards the Pashtuns living in the tribal areas bordering Pakistan.

The Tajik and Uzebk ethnic groups though have historically not been able to dominate Afghanistan, a Pashtun majority country. And since India has no borders with Afghanistan, it is not possible for her to intervene or secure her national interests without first physically over-running a nuclear armed Pakistan. Hence the impasse in Afghanistan!

India, of course, could not just accept that. The corollary is, Pakistan will not back off either. Both India and Pakistan have historical claims and substantial influence and engagement in Afghanistan. Resolving earlier geo-political conflicts, therefore, is key to a future of peace in Pakistan and relations between India and Pakistan must necessarily improve for that to happen, if and when it does. The end to the war in Afghanistan, therefore, can begin only after peace between India and Pakistan.

I comment each time I like a post on a website or if I have something to valuable to

contribute to the conversation. It is caused by the

fire communicated in the article I read. And after this post India & Pakistan Relations: Implications for Afghanistan – Global South.

I was moved enough to write a thought 😉 I actually do have a

couple of questions for you if it’s allright.

Is it only me or do a few of these comments come across like

they are coming from brain dead people? 😛 And, if you are posting

at additional social sites, I’d like to follow anything fresh

you have to post. Would you list every one of your communal sites like your twitter

feed, Facebook page or linkedin profile?

[…] India & Pakistan Relations: Implications for Afghanistan […]

[…] India & Pakistan Relations: Implications for Afghanistan […]

[…] India and Pakistan Relations: Implications for Afghanistan by Khalid Hussain […]

[…] India and Pakistan Relations: Implications for Afghanistan by Khalid Hussain […]

Indeed. “The end to the war in Afghanistan, therefore, can begin only after peace between India and Pakistan.”

Wonderfully argued…