l.By MANOJ BHUSAL & SAILA OHRANEN

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s sovereign states, countries are free to decide whom to welcome inside their territories, but if global responsibility is a part of the puzzle, many countries in Europe will have to do a serious soul-searching to recover from what we might call now a pervasive compassion fatigue.

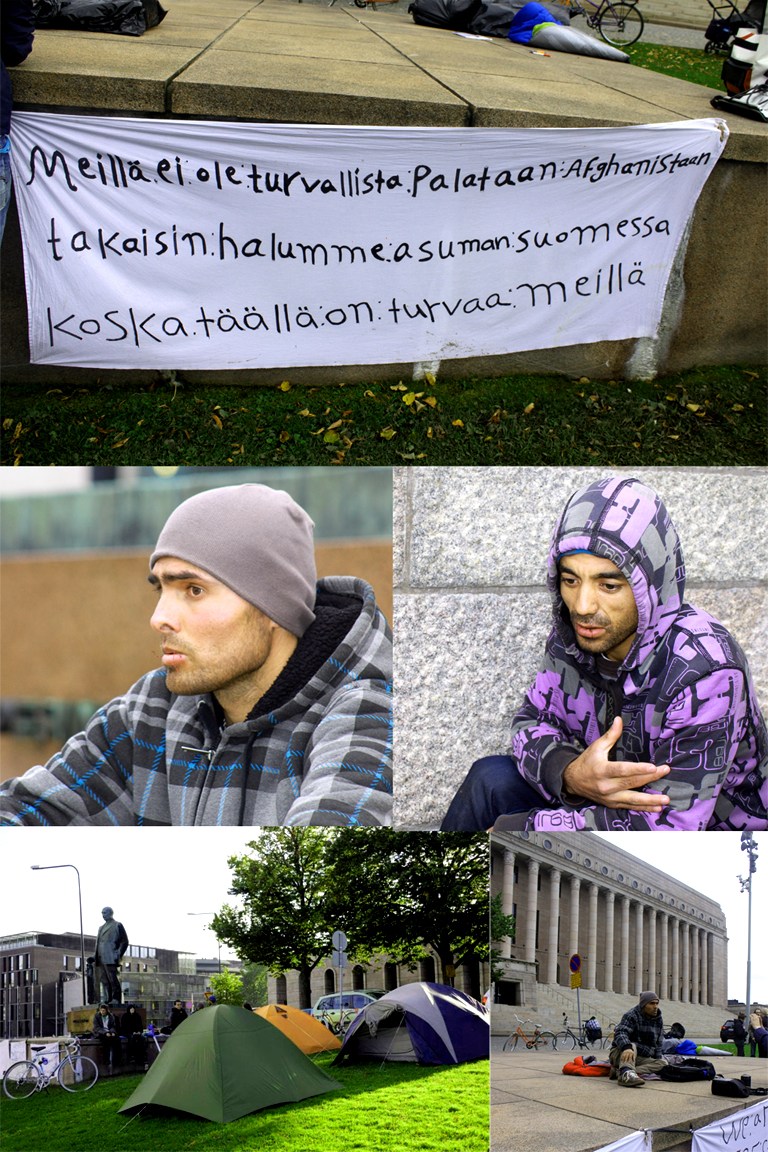

Monday evening this week, when we reached the Finnish parliament premises for this story, three middle-aged Afghans, pale and exhausted due to already a week-long hunger strike, were struggling to speak to a tiny number of journalists that surrounded them. As a symbolic gesture of protest, they had sealed their lips, but on request of the press, the knots were loosened and the men agreed to speak.

After their asylum applications were rejected by the Finnish authorities stating that it is safe to return to Afghanistan, the men had decided to go for an indefinite hunger strike, organizing a loose ‘open sky’ camp in front of the Finnish parliament building. Though media coverage has been scant; the men have been there for more than a week already; reportedly, without drinking and eating anything. On Tuesday, it was reported that they received three tents from Finnish NGOs as the men are on strike 24/7.

“They said the danger is for women and little children, not to men like you,” said one of the protesters, swapping his dry lips, “But that’s not true. Afghanistan is my home country and I know it better. If my country was safe, I would go back to my country on my own. Nobody would need to deport me.”

“I know why I am not in my home country, but wandering around in foreign lands. I know how insecure it is to live there. If one’s country is safe, nobody wants to live as a refugee by will,” he added.

The men fear prosecution for political reasons. Mirzai is a citizen activist, Gholam has lost his son and brother due to political activities of the family and Shamsud is afraid of revenge due to his brother’s death.

See Also: The 7 Misconceptions About Refugees & Refugee Camps

According to the United Nations more than 3000 people were killed in Afghanistan in 2011 alone, many of them innocent civilians. According to the Global Peace Index 2012, Afghanistan is the second most dangerous country in the world, after Somalia.

“It is very dangerous in Afghanistan. The Taliban is still there and the government kills its own people,” said Mizrai, “we have been here for more than a week without food and water, but only one question: would you please understand us?”

The men resent that they were not really heard and understood in the asylum trials. “Nobody really heard what we had to say. Nobody was keen to hear our stories,” said Shamsud, “Even our translator said he knew what type of people we are so there is no need to speak much.”

“Even here, parliamentarians and ministers pass by everyday, but they haven’t even asked why we are here. Instead, police has been used to frighten and route us out,” he added.

During our meeting that lasted little less than an hour, the protesters shared harrowing tales of their bitter past. Mizrai said he had lived almost his whole adult life as a refugee, more than 30 years in Iran, where he couldn’t even buy a telephone SIM because he was a refugee, before finding his way to Europe. “We thought things were different in Europe, and we thought we would be understood and protected here,” he said, with tears dabbling in his sunken eyes. Shamsud remembered his friends who had died en-route while trying to cross stringent borders.

Complex Immigration Politics

Finland, otherwise one of the most competent and termed sometimes even as the best country in the world to live, finds itself in difficult terms when it comes to immigration issues. Finland does accept UN quota refugees annually, but the number has been significantly low when compared to its Scandinavian neighbors. Number of asylum applications have decreased in recent years while the number of deportations have increased steadily.

“Our quota system seems to be like a lottery game. I know people who have been deported even in very dangerous situation,” says a Helsinki based freelance journalist we met in the parliament premises, “ One one hand, we want to save our international image as a generous country firmly committed to global responsibility, but on the other hand, we have to struggle with our own insecurities, rising right-wing radicalism and exhaustively technical bureaucracy.”

Asylum regulations have been changed and been made tougher in recent years. For instance, people can be deported even if some regions in conflict affected countries are deemed safer. However, these assessments are not always clear and up-to-date.On the other hand, single reasons such as torture are not enough to grant an asylum.

In June this year, Pekka Tuomala, the director of the Centre for Torture Survivors in Finland accused the Finnish Immigration Service of callous disregard for torture victims. Reportedly, dozens of asylum seekers had their applications turned down and were deported back to their country of origin, in disregard of the United Nations Convention Against Torture. According to the UN convention, torture victims should not be returned to the country where they were tortured.

Whereas, in the last few months, the European Court of Human Rights and the UN’s committee on torture were able to stop the deportation of some asylum seekers from Finland, reports the Finnish broadsheet Helsingin Sanomat.

General Public and the Supreme Court

While public opinions on asylum issues seem to be divided in Finland, with a significant majority taking somewhat an indifferent stance at least in public, there are strong minority groups who either strongly support or oppose the phenomenon.

In March 2012, when Antonio Dalas, an Angolan young man, was deported back to Angola, and was imprisoned there, it created an outrage in Finland. Finnish supporters of Antonia Dalas even warned to launch a criminal complaint against immigration authorities. A Facebook campaign for Antonio Dalas’s asylum support attracted a significant number of supporters.

See Also: Syrian Refugee: ‘I don’t want to die’

In another incident in April this year, a Zimbabwean homosexual man; who had lived in Finland for more than ten years, had already sought asylum three times, but was consistently rejected; was ready to be deported. This time, however, the Finnish Supreme Court intervened on grounds that homosexuality is illegal in Zimbabwe, punishable by fines and imprisonment.

While a group of Finnish activists and the Supreme Court have been able to prevent such deportations, there is still another strong minority of radicals, campaigning mainly online, that opposes any form of immigration to Finland.

A UNHCR report released in June this year reveals deep imbalance in international support for the world’s forcibly displaced, with a full four-fifths (80%) of the world’s refugees being hosted by developing countries. “Poor countries host vastly more displaced people than wealthier ones. While anti-refugee sentiment is heard loudest in industrialized countries,” noted UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in his message on World Refugee Day.

As sovereign states, countries are free to decide whom to welcome inside their territories, but if global responsibility is a part of the puzzle, many countries in Europe will have to do a serious soul-searching to recover from what we might call now a pervasive compassion fatigue.

The fate of these three Afghan men is uncertain, but the world is closely and curiously watching: what is going to happen to these men as they camp for justice in the heart of Helsinki. It is difficult to say if this incident will enable people to see the root causes and reasons behind this case in particular, and immigration in general or despite everything a mysterious silence and indifference will prevail.

(We thank our translator Amiir for making our conversation possible with the protestors. We can be reached by emails [email protected] and [email protected])

(If you want to show your support to the case of the three protesting Afghan men, you have an opportunity to participate! A demonstration is going to be organized on Friday, the 21st of September starting with a gathering at 2pm by the statue of three blacksmiths at the center of Helsinki (Kolmen sepän aukio). From there the demonstrators will march to the Parliament House (eduskuntatalo) where a demonstration will take place. More information about the program can be obtained from http://vapaaliikkuvuus.net)

(If you want to show your support to the case of the three protesting Afghan men, you have an opportunity to participate! A demonstration is going to be organized on Friday, the 21st of September starting with a gathering at 2pm by the statue of three blacksmiths at the center of Helsinki (Kolmen sepän aukio). From there the demonstrators will march to the Parliament House (eduskuntatalo) where a demonstration will take place. More information about the program can be obtained from http://vapaaliikkuvuus.net)