By Anna Heikkinen

By Anna Heikkinen

[dropcap]G[/dropcap]uatemala ranks as one of the poorest countries in Latin America, as over half of the Guatemalan population, 53.9%, lives under the poverty line, of which 23 percent struggle in extreme poverty. The poverty is centralized in a so-called “poverty belt”, an area stretching by the West-North axis of the country. The “poverty belt” is mainly populated by indigenous people, and was seriously affected by the 36-year long Guatemalan Civil War, which finally concluded in 1996.

Due to high level of deprivation in Guatemala, the indicators of social progress, such as child malnutrition and mortality, illiteracy and primary school incompletion rates are alarming. According to the Centre for Economic and Social Rights (CESR), an international human rights organization combating economic injustices globally, in Guatemala approximately 50 percent of children under five are chronically malnourished.

The number is the highest in Latin America and the fifth highest in the world. Despite the government’s commitment to combat poverty and child malnutrition in the Peace Accords of 1996, the rate of undernourished children has risen significantly. In addition, the child mortality rate in Guatemala is also one of the highest in Latin America. Statistics show that children living in rural areas or having indigenous background, and children whose mothers had no formal education, have higher probability of dying before age five.

Guatemala also notably underperforms in literacy compared to its counterparts in Latin America with equivalent GDP per capita. Since the mid-1990s, Guatemala has succeeded in increasing the adult literacy rate, for instance, in 1990 only 61.5 percent of population age 15 and above were literate while in 2015 the rate had climbed to 81.5 percent. However, the differences in literacy between regions, gender and ethnical groups remain significant: in 2006, only 68 percent of indigenous women living in rural areas were literate while the number was 96 percent for non-indigenous women in metropolitan areas.

Only one out of three children in Guatemala completes basic education. In 2015 only 45.6 percent of children continued to study in secondary school and as few as 23.9 percent were still enrolled in college. The rates are not very encouraging specially when compared to other Latin American countries. These figures are, in fact, weaker than in Honduras and Bolivia, countries with lower GDP per capita than of Guatemala. The gap in primary school completion rates between geographical locations, gender and ethnic groups is also striking. The disparity between boys and girls completing primary school in Guatemala is the widest in entire Latin America. In rural areas, only 36 percent of girls and mere 14 percent of indigenous girls finish primary school.

You May Also Like: There is Hope for Guatemalan Children, They Should Stay Home

In 2008, Guatemala launched a free educational program. Since then, it has achieved a significant progress in school enrollment rates: in 2015 the national average of children from 7 to 12 years enrolled in the primary school was 81 percent. Nevertheless, low school attendance, high repetition and dropout rates remain national concerns.

The underlying reasons for children leaving school are the indirect costs related to going to school, poorly qualified teachers, poor infrastructure and lack of bilingual education. On the other hand, lack of interest, health and economic reasons were the principal causes for dropouts from primary education. Economic reasons, within which boys mentioned paid jobs and girls household tasks, were dominant for dropouts by the shift from primary to secondary school. Primary education in Guatemala is mostly public, while over half of the secondary schools are private.

There have been some attempts to address the high dropout rates by the government. In the mid-1990s, a scholarship program was launched to enhance school enrolment and reduce dropouts especially in rural areas. The government has also introduced school food programs to give incentive for children to attend school. However, the programs have not had wished success in reaching their objectives due to insufficient and uneven distribution of resources. Most of all, the programs failed to target the aid in the most marginalized regions where the number of children not regularly attending or completing primary school is the highest.

You May Also Like: Los Vigilantes in Guatemala: When State Security Fails

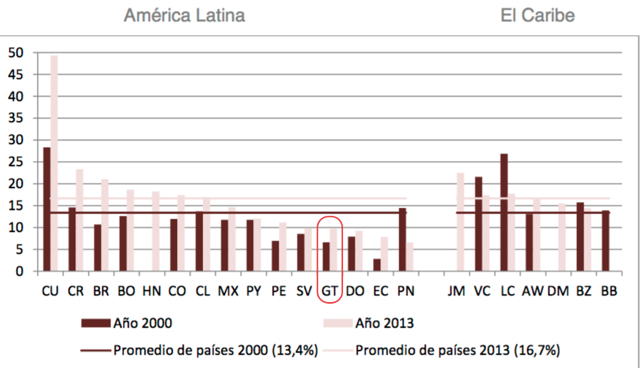

The public investment in education in Guatemala remains among the lowest in Latin America. In 2013 the share of annual budget for education in Guatemala was 3 percent of GDP while in the rest of Latin America, the number remains at 5.6 percent. For example, the annual budget of Ministry of Education of Guatemala, to maintain the school infrastructures was, in 2009, approximately 1,500 quetzales (US$180). In addition, allocation of education budget between urban and rural regions is extremely unequal.

Guatemala is among the most successful economic performers in Central America with a GDP growth rate of 4.1 percent since 2015. Nevertheless, the country generates relatively small proportion of income from taxation. In the 1996 Peace Accord, Guatemala committed to increase its tax base to have adequate resources to implement the longed improvement on its health and education sector. However, since 2003 the tax rate in Guatemala has not significantly increased and remains one of the modest in the region. The major part of the tax revenues in the country is collected from indirect tax on consumption. On contrast, the rate of direct taxation on income and assets in Guatemala is one of the lowest in the world.

A study by the World Bank shows that education plays a crucial role in combatting chronic poverty and preventing transmission of deprivation between generations. Low level of education has also shown to correlate with high unemployment, low wages, malnutrition, weak health and child mortality. Especially girls are prone to inherit the poverty from their mothers, and are in bigger risk to child marriage, give an early birth and have larger number of children. This further feeds the poverty circle since the largest families in Guatemala tend to be the ones struggling the most with poverty.

Schooling has been shown to give competencies that enable access to better employment and higher salaries. Moreover, every additional year of education brought approximately 10 percent increase in salaries. Intervention in education is not only vital to dig the way out of poverty on an individual level, but it also brings substantial economic benefits to society as a whole. Risen achievement in education of a country’s population by one year has showed to increase annual per capital GDP growth by 0.5 percent and consequently, resulted a growth in per capita income by 26 percent over a 45-year period.

Considering that only twenty years have passed since the end of the civil war, Guatemala has managed to take notable steps fostering its economic and human development. However, inequality and poverty still remain at concerning level. The efforts of Guatemalan government to tackle the problem have already borne some fruits, and today universal primary education and enrollment rate coverage countrywide have almost been achieved. However, much is still left to be done. With the current rate of public spending on education, it will impossible to address the alarming drop-out rates, to implement highly required improvements in quality of schooling and monitor that a fair share of the schooling budget reaches the most remote areas. Education is a human right and a proven passport out of poverty. Investing in education is what Guatemala urgently needs to raise its people out of poverty and continue the success story of its economy on a sustainable basis.

(Heikkinen holds a master’s degree in Global Political Economy from Stockholm University and BSc. in Environmental Economics from the University of Helsinki. She has researched the impact of climate change on poverty in Peru and recently worked in a sustainable development project promoting education to tackle poverty in rural areas in Guatemala.)