By Mark Malloch-Brown

By Mark Malloch-Brown

SDG 10’s inequality is not a ‘nice to have’ policy abstraction; rather it will determine all our futures.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]nequality almost did not make it into the 2015 United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The earlier Millennium Development Goals had stopped at poverty reduction – deemed a safer, less controversial objective. And in the early stages of drafting the SDGs there was still reticence in some quarters; a fear it was a divisive issue. But, in the last few years, inequality has raced up the political agenda. It’s no longer just about the injustice of very poor countries with rapacious ruling elites. It’s suddenly about all of us. Whether it was the UK referendum vote on leaving the EU, the US Presidential Campaign or indeed politics everywhere and anywhere, the division between those at the top and those whose incomes have fallen and stagnated has become the organising force of politics.

So SDG 10, which almost didn’t make it, is now as central to development as the fight against absolute poverty was when I and others drafted the original goals. But if there is wide agreement that inequality now poses a direct threat to the stability and health of societies, there is less agreement about what to do about it.

The classic European policy response is to use the redistributive power of taxation. Tax high-income earners and recycle this in the form of social services such as health and education, welfare and income support to the less well off.

Obviously, even in Europe, the effectiveness of this is disputed. It did not, for example, stop a Brexit vote. In much of the developing world, it is anyway a non-starter because the proportion of GDP gathered in tax is much smaller and the inequality gap much wider. There simply aren’t the resources available to redistribute.

Nor does it get to the core of the inequality which is not actually about unequal earnings so much as it is about the division of so many developing countries into modern and traditional economic sectors. In the first, an urban elite accumulates savings, enjoys a western lifestyle with all the trappings and captures most of the benefit of the high economic growth rates that many developing countries have enjoyed in the last decade or so. At the same time, most of their fellow citizens eke out a living and remain trapped in either an informal urban sector of marginal employment – slum living and failing infrastructure – or in many places an increasingly inefficient over-populated agricultural and rural sector.

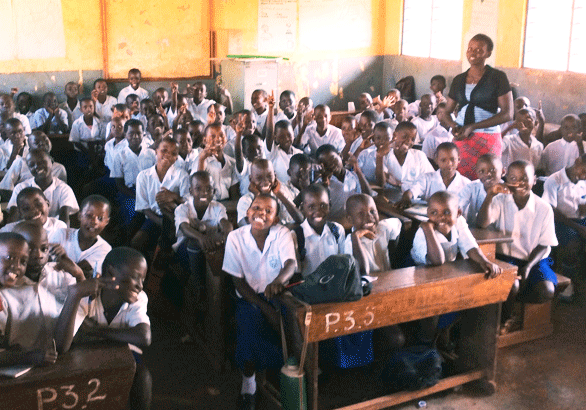

The real answer to inequality in developing countries is to expand that modern sector: create decent, well-paying jobs off the back of a competitive urban economy of manufacturing, services and a similarly efficient rural sector. For Africa particularly, with the prospect of a doubling of the population in short order, this has become an imperative. By 2025, it too like the rest of the world will have exceeded 50% cent urbanisation, yet there is little sign of jobs and infrastructure keeping up with this prospective demand. And the population explosion of cities in South Asia offer a dire warning of the social and human costs when the housing, sanitation and clean water, transportation, let alone the jobs are not there.

So it is engineers and entrepreneurs, not tax collectors, who at this stage hold the key to reducing inequality in much of the world. We have to find ways of building inclusive, productive economies on a platform of sustainable energy and infrastructure. And so for now, the key issue is how to leverage and scale up domestic and international private capital on a scale that matches up to the challenge.

I chair the Business Commission for Sustainable Development which has assembled a group of business leaders from around the world representing multinational as well as local SMEs to advocate for the extraordinary opportunity and responsibility that the private sector confronts. Business as usual means mounting inequality, increasing insecurity and environmental and other risks and a smaller global market as billions of people are left behind in the old economy. On the other hand, finding business models that allow proper financial returns on sustainable infrastructure development and job creation in the developing world could offer us all a much larger, more prosperous, sustainable and inclusive world. SDG 10’s inequality is not a ‘nice to have’ policy abstraction; rather it will determine all our futures.

(The Right Honourable The Lord Mark Malloch-Brown KCMG PC is a former UK government minister and United Nations Deputy Secretary-General.)