Due to climate change-driven rising flood waters in Bangladesh workers are leaving their land and moving to the country’s cities in their droves.

Seasonal flooding by the melt waters of the Himalayas is a natural phenomenon. Today, however, the amount of water reaching the low lying rivers of Bangladesh seems to have reached epic proportions.

The sea is advancing inland, flooding vast areas. Protective embankments—damaged and destroyed by recent cyclones Sidr and Aila in 2008 and 2009—offer little or no resistance. In some places sea defences have disappeared altogether and no new embankments are being built or repaired. Whole areas of agricultural land are submerged.

This is complicated by the widening of rivers due to the large volumes of water descending from mountainous areas where glaciers are shrinking.

These are the low lying areas populated by the landless poor where no one else wants to farm. Some NGOs have advised building houses on higher ground and raising the level of planted areas, but this is labour intensive and does not produce food in the short term. Expensive machinery needed to repair the banks to make these lifesaving modifications is in short supply. The rural poor are the hardest hit—forced to pack up as much of their belongings as they can carry to seek employment elsewhere.

Farms engulfed by rising rivers

Farms engulfed by rising rivers

Rural villages are inundated by swollen rivers and the ingress of sea water with high levels of toxic salt making agricultural production impossible.With no fields left to farm, the farmers are giving up and making the journey for work to already crowded, over populated, and sprawling cities. One such destination is Dhaka. The vast megacity is located in central Bangladesh, which continues to grow apace as half a million rural refugees join the ranks of the slum dwellers each year.

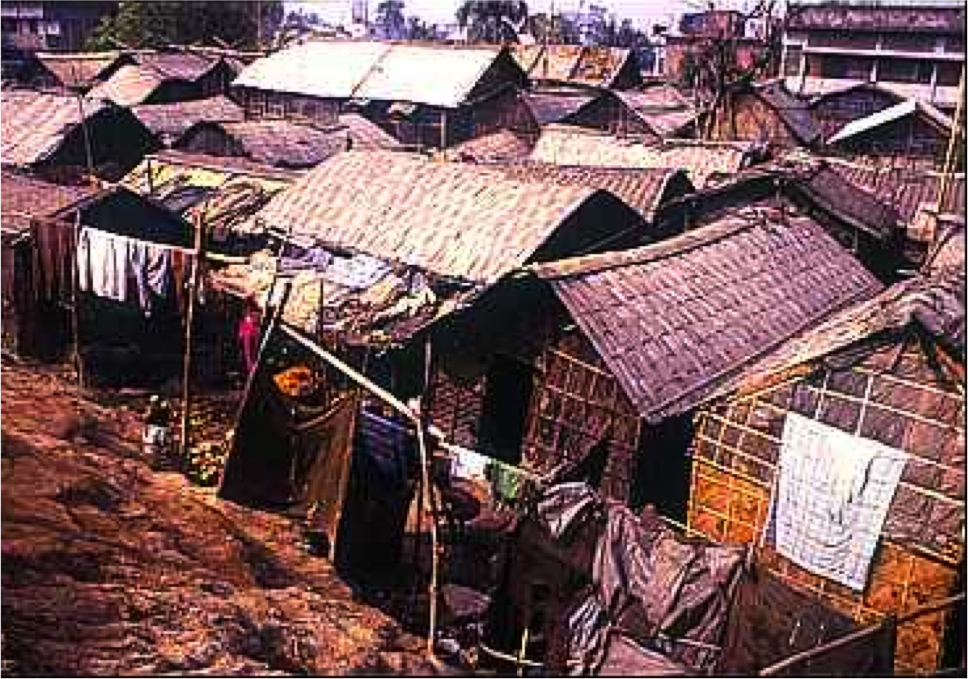

Dhaka’s slums are made up of five major clusters. Korail is Dahka’s largest colony consisting of nearly twenty thousand ramshackle ‘Jhupri’—crude and primitive dwellings of corrugated iron and bamboo walls or simple rudimentary shelters covered with plastic sheeting. A typical living space averages three by five metres and is inhabited by extended families—usually grandparents, uncles, aunts, parents, children, and new born babies. The shelters are used for cooking, cleaning, and washing, and are typically interspersed by narrow alleys and bisected by drainage channels taking away excrement and waste water. These open sewers block and spill over into the passage ways where children play and food is prepared. Children accustomed to the putrid stench, occasionally blotted out by the smell of cooking, play with bare feet amongst the throng of traders lining the busier walkways selling their vegetables, kitchen utensils, and cheap cosmetics. The scene is dotted with brightly-clad women in saris that are cutting hair, drawing henna art, or are engrossed in their sewing machines making and repairing garments.

Forty per cent of Dhaka is sub-standard housing

The number of Bangladeshi’s slum dwellers totals over 5 million with major populations in and around the principal cities of Dhaka, Chittagong, and Khulna, at a density of up 4,210 per acre, or 2.7 million per square mile (1 million per square kilometre). 40% of Dhaka’s population occupy government-owned land. The city ‘slumscapes’ are a familiar sight for office workers using Dhaka’s roads and railway as they commute to work. The ghetto clusters are the size of large towns with their own councils and political representatives.

Rural people of the Char region in Southern Bangladesh have made a habit of migrating to Dhaka during the Monsoon rains on an annual basis. The megacity is used to the seasonal influx of rural workers who are trying to find alternative employment among the residents until the rainy season passes, the floods subsides, and they can return once again to their land and farm for living

But now they are not returning to their homelands as the rivers remain swollen, never returning to their original levels and swallowing up vast swathes of fertile land lining the banks.

Homeless farmers turn to the slums

Homeless farmers turn to the slums

The Dulal Khan is just one of the many farmers who were made homeless. They left their village in Chandpur district which is located at the mouth of the Meghna River. Dulal squats to recount his story while his relatives crowd the family bed in his tiny tin roofed ‘Jhupri’ watching and listening.

He gesticulates with his wizened hands as he explains:

“This is my life, I gave up growing vegetables which I used to sell to make a living. My vegetables wouldn’t grow when the water went away”

His family watched from the barely lit room, the light from a single low wattage light bulb leaving half his face in dark shadow. His meagre possessions include a small cupboard to keep the dishes and an old TV perched precariously on top.

But, despite their crowded conditions, Dula, his wife Samima Begum, and three children—Suma age seven, Sumon age eight, and four year old Manik—see themselves as better off than most other slum dwellers.

When he moved to the Baunia complex six years ago, he managed to find a job working in a readymade garment factory,

Dulal continues:

“I found a job in a factory but when the work dried up I lost my job. I began to work on a building site, but after six months the site closed and I was able to set up my tea business with the money we saved.”

Dulal Khan now works as a tea vendor at a local bazaar. He and his family live near a bustling lively street where his offspring attend a school for slum dwellers and their children.

“There are far more opportunities here than the wastelands of Chandpur back home” Samima says, Mr Khan carries on: “there is no reason for me to go back, my children have a school and I have made a living here, there was nothing left for me there [in Chandpur].”

Dulal Khan sees himself as one of the more privileged slum dwellers—compare his lot with Ali Hossain and his family. They too were rural farmers from the same district of Chandpur. Ali Hossain left his farm to join his relatives already living at the Pallabi slums of Mirpur, in Dhaka, where he runs a small vegetable selling business. He brought his wife Momoto Banu and their five children to the complex, where together they live as an extended family of fourteen members. Under the same makeshift roof are aunts, uncles, nephews, and nieces—adults and children living in cramped and squalid conditions as well as grandparents. As poor farmers they were only making enough money to survive—they could only grow enough to eat, with hardly any left over to sell.

Typhoons followed by monsoons

Ali, surrounded by his four sons and daughter aged between four and fifteen, remembers the disaster vividly that led to their exodus from the place where he was born:

“the typhoon came, we ran to the shelter, when we went back to the fields my crops were ruined, our village was flattened.”

Momoto nods in the background as Ali tells of the horror indelibly etched in his memory:

“Monsoons flooded the land, the river came up and swept away the collapsed buildings so we couldn’t rebuild. My fields remained under water once the monsoons had finished as water levels didn’t return to normal. Usually I can plant my rice but the water was too deep—we came to my brother’s and we have been here ever since, there was nothing to go back for.”

Rural districts are becoming ghost lands as more and more people head for towns and cities.

Ali continued:

“More of us are staying, the rivers are widening, eating up the fields and even the villages that line the banks. Some people are trying to farm differently with the help of NGO’s, they are building their houses higher up on mounds of earth and planting in banked up areas, but they are too small for them to grow enough to sell, there is only enough vegetables to eat, I had no choice but come to my brothers in Pallibi.”

Illnesses caused by contaminated water

The Dickensian conditions of the slums contribute to family illnesses and prolonged bouts of diarrhoea. Ali’s nine year old daughter Liton constantly suffers from diarrhoea, fever, and vomiting. Ruman, one of his sons doesn’t go to school because his mother is too worried about his health.

“I am sick all the time,” says Ruman. “Even today I have had some diarrhoea.”

His grandmother Hasina added: “Someone or other is always sick, as soon as someone starts to get better, someone else falls ill.”

Ali’s family have to draw their water from the same place as their toilet. All fourteen members of the same family use the toilet situated below the water pump.

It is evident that this story is being repeated over and again throughout Bangladeshi slums with cooking in close proximity to raw sewage running in open drains as well as cross contamination with drinking water.

City people expect rural workers to converge on Dhaka looking for work during the rainy season, however, they are also used to them going back to their fields after the floods subsided. This has always been seen as a benefit to the better-off who employ the slum people as maids, servants, and as other forms of cheap labour. Many of the ghetto people are rickshaw pullers and sweepers who are essential in the transport sector, driving people across the city and keeping the streets clean—Dhaka wouldn’t be able to function without them. (>>Continue Reading)

International community should act right away to help Bangladesh fighting climate-change effect while still there is time.

[…] yet they realize that the growing slum sprawl and strain on basic services are unsustainable. The slum population in Bangladesh numbers over five million and is largely spread around clusters in Dhaka, as well as […]

[…] yet they realize that the growing slum sprawl and strain on basic services are unsustainable. The slum population in Bangladesh numbers over five million and is largely spread around clusters in Dhaka, as well as […]

[…] Climate Change Drives Rural-Urban Migration to Dhaka’s Slums […]

[…] Climate Change Drives Rural-Urban Migration to Dhaka’s Slums […]

The editing hasn’t brought out the point that poor workers from flooded farmland looking for work are swelling the ranks of the slum dwellers. Tthey are not returning home to their land to take up farming again as fields remain under water,. When the floods recede rivers have changed their courses and are also wider swallowing up more areas of agriculture.

David Meagher – Author

[…] Change and Gender Inequality in Bolivia: Why We Need Sustainable Development « Previous / Next » By thedevelopmentroast / August 2, 2012 / Climate Change, Women / Leave a […]

This article has left me speechless. it resonates with what a Bangladeshi Minister said in Rio at a side event that helped me understand the climate change challenges in this region. The time for the international community to act seesm to be running out!