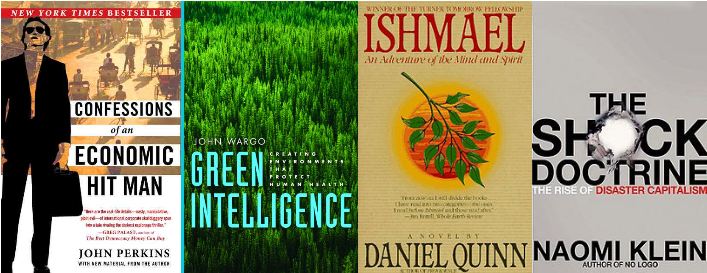

I tend to get pretty depressed after reading many economic, international development and environmental books—factual, fiction or otherwise. If you do not know what I mean, I highly recommend reading Daniel Quinn’s 1992 novel Ishmael. Set up as a conversation between a teacher and student, where the former happens to be a hyper-intelligent, talking Guerrilla, the book slowly takes the reader through environmental philosophy reasons for how we have managed to get ourselves into the present day environmental mess. Upon turning over the last page I felt empty and angry at everyone, especially myself. Being on vacation in El Salvador and staying in an air-conditioned hotel room with an outdoor pool, which already felt pretty uncomfortable, all of a sudden felt like a ridiculous extravagance that was killing the planet. I immediately understood why one reviewer had said: “From now on I will divide the books I have read into two categories — the ones I read before Ishmael and those read after.”

I tend to get pretty depressed after reading many economic, international development and environmental books—factual, fiction or otherwise. If you do not know what I mean, I highly recommend reading Daniel Quinn’s 1992 novel Ishmael. Set up as a conversation between a teacher and student, where the former happens to be a hyper-intelligent, talking Guerrilla, the book slowly takes the reader through environmental philosophy reasons for how we have managed to get ourselves into the present day environmental mess. Upon turning over the last page I felt empty and angry at everyone, especially myself. Being on vacation in El Salvador and staying in an air-conditioned hotel room with an outdoor pool, which already felt pretty uncomfortable, all of a sudden felt like a ridiculous extravagance that was killing the planet. I immediately understood why one reviewer had said: “From now on I will divide the books I have read into two categories — the ones I read before Ishmael and those read after.”

The simple lack of available information or transparency around the use and effects of chemicals in every product that surrounds our lives—as well as more blatant and grievous releases of chemicals into the environment by army weapons testing and other industries—exposed by Yale Professor John Wargo in his 2011 book Green Intelligence left me feeling paralysed. The massive private efforts to shut the public out and the inadequate policies and regulations in place to hold businesses responsible for polluting the environment and human beings to the point of disease and death was devastating—I just had no idea what I could do.

The 2004 Confessions of an Economic Hit Man was one of only two books that ever made me literally weep upon finishing it. I remember the moment vividly as I shrank deep into my long-haul flight airplane seat and quietly sobbed on my route to do fieldwork in Guatemala. The book is a personal life history exposé by John Hopkins that claims that he, and many people like him, were used to convince the political and financial leadership of underdeveloped countries (often using false projections) to accept enormous development loans from institutions like the World Bank and USAID that saddled them with an impossible debt and perpetual under-development—while the developing countries had to pay back loans with interest to U.S.-dominated institutions, they were contractually obligated to use U.S. firms for the projects that were the purposes of the loans to begin with, thus making sure that internal development would not, in fact, occur.

Naomi Klein’s 2008 The Shock Doctrine—a carefully researched and documented behind-the-closed-doors story of how American “free-market” policies have come to dominate the world through exploitation of disaster-shocked peoples and countries—had a similar, sinking effect. I simply felt powerless to be able to affect a change when so many of the world’s inequalities and injustices seemed to be purposely orchestrated by a powerful few that are unreachable to so many of us.

And there are many more book examples like that—all with one thing in common: I felt worse than before and immobilised after reading them: I had no idea where to start.

Then, through serendipity more than plan, I began to slowly see things differently. Living and working in different countries like Bolivia, Thailand, Nicaragua and Guatemala, for example, I saw many hardships, but also many small victories that ordinary people were winning by improving their lives and the lives of others. The sheer passions and determination that Edwin showed—a gentle giant of a man, an artist and a teacher who found a dream job working for an educational NGO in Guatemala—was simply inspiring. He worked long hours and weekends, through harsh weather, illness and personal trauma, not because he has to got to work, but because he wants to help his indigenous Maya community.

Then, through serendipity more than plan, I began to slowly see things differently. Living and working in different countries like Bolivia, Thailand, Nicaragua and Guatemala, for example, I saw many hardships, but also many small victories that ordinary people were winning by improving their lives and the lives of others. The sheer passions and determination that Edwin showed—a gentle giant of a man, an artist and a teacher who found a dream job working for an educational NGO in Guatemala—was simply inspiring. He worked long hours and weekends, through harsh weather, illness and personal trauma, not because he has to got to work, but because he wants to help his indigenous Maya community.

My recent involvement with Worldwatch Institute’s Nourishing the Planet project was also enlightening. Recognising that the current global systems are not sustainable and are, in fact, destroying people and the planet, it highlights individuals, initiatives and organizations that are striving to make a difference. The projects are often small, started on someone’s spare time, with little funding but a ton of commitment, enthusiasm and heart. Yet, they are making huge differences in people’s lives and in improving the environment.

I also began reading books and works with the objective of looking not only for problems, but good, practical suggestions on how to solve them. For this issue I reviewed Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social and Ecological Intelligence, written by Daniel Goleman, Lisa Bennet and Zenobia Barlow of the Center for Ecoliteracy. It tells eight stories that start by outlining problems of injustice, corruption and pollution that pertain to such things as the awfully destructive mountaintop mining; poverty and unfairness in distribution of resources and quality of education in schools; and environmental and social destruction of oil drilling in indigenous people’s traditional home environments. Yet, the bad news only sets the scene and the book is a revelation of practical action that individuals and communities—including children and youths—are making in their fight for a better world.

My most recent foray into Fred Magdoff’s and John Bellamy Foster’s 2011 What Every Environmentalist Needs to Know About Capitalism also surprised me as, after a long description of how things have gone wrong, the book ends with a long chapter on what activists, academics, policy makers and normal people should and can demand to help change things around.

As I began to get more and more inspired, the words of Ghandi—recounted to me by a close friend—really helped put things in perspective. “Be the change you want to see,” he said when, in turn, quoting his own grandfather. So I have decided to make a pledge to no longer be inactive or feel paralysed because the size of the problem seems too big for me to make a difference. We can all make small changes and, as part of the GSDM inspiration issue, I pledge to do everything I can—within the time that I can spare and within the confines of the changes that I can realistically make—to make sure that my life reflects my ideals as much as possible. I will carry a thermos flask to make sure I never buy a bottle of water or take my coffee to go in a throwaway paper cup. I will carry a reusable shopping bag to make sure I never use a plastic one. I will not buy clothes unless I absolutely need them and I know that they are sourced and made responsibly. And, locally, I will work to improve my community and be a greater advocate for sustainability, social justice and the future of humanity. Join us, feel inspired and feel empowered to make a change. After all, as the zen saying goes: “Happiness if when what you think, say and do are in harmony.”

Ioulia Fenton leads the food and agriculture research stream at the Center for Economic and Environmental Modeling and Analysis (CEEMA) at the Institute of Advanced Development Studies (INESAD) in La Paz, Bolivia.

What is your pledge? Share in the comments below.

This article originally appeared in the October 2012 issue of Global South Development Magazine that focused on inspiration.