By Aubrilyn Reeder

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]ubrilyn Reeder oversees integration of well-being and happiness metrics into infrastructure development and management at United World Infrastructure (UWI).

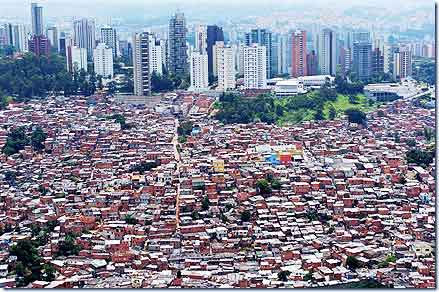

Before its well-earned sigh of relief, Rio de Janeiro should savor another 2016 Olympic feat – apart from Brazil’s volley ball and soccer teams, and its two new gymnastic stars, Rio showcased the mettle of a vibrant city. The city, and state and country, must still navigate a challenging path forward; but lessons from recent transformative infrastructure investment initiatives in the “favelas” can greatly enhance the quality of life for the city’s poorest residents, in a lasting way, and serve as a metropolis standard bearer

Rio’s “favelas,” or informal settlements, house 1.5 million or 24-25 % of Rio’s population. Rio announced a USD 2.8 billion investment in 2010 from federal and state funds and a loan from the International Development Bank – to upgrade favelas by 2020. This follows a federal USD 1.9 million investment in large-scale favela infrastructure projects and new police pacification units (UPP) to re-establish security.

Brazil’s modern path in prioritizing citizen happiness via improved social, economic, and environmental wellbeing dates back to 1992, when it hosted the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) and, more recently, the 2012 Gross National Happiness Conference. But the past two years of Brazil’s Olympics-related development has been accompanied by a crippling economic recession.

Despite vast improvements, development goals for the favelas fell short, and the media has highlighted the consequences: forced evictions, crime, and pollution of Olympic open water venues.

Improving the quality of life in slums, which count for 25% of the world’s urban population, is critical for improving the social, economic, and environmental happiness for cities. The U.N. identifies slums as: having inadequate access to sanitation and infrastructure, poor structural quality of housing, overcrowding, and insecure residential status.

Rio’s favelas would not all qualify as “slums.” While not meeting city code, many homes were erected by residents with experience in construction, and some have running water, electricity and internet access. Some urban romanticists describe the organic nature of the favelas as central to their sense of community, entrepreneurial spirit, and creativity. A recent survey by Data Popular reports 85% of favela residents liking where they live; 70% would stay even if they doubled their current income.

Yet sewage and sanitation remain a big challenge. Tuberculosis and infant mortality rates in favelas are much higher than elsewhere in Rio. Life expectancy is at 56 years, compared to 74 years elsewhere in Brazil. Crime is rampant; 37% of the favelas are controlled by drug trafficking.

See Also: Climate Change Drives Rural-Urban Migration to Dhaka’s Slums

Still, many residents want to live there for the same reason people of all backgrounds are moving back to cities– opportunity. By 2050, 2.4 billion more people around the globe will live in cities, a 60% increase from today, and informal settlements provide an affordable housing option and proximity to jobs.

Pre-Olympics, Brazil strove to re-develop, resettle, and upgrade favelas with deference to residents’ rights, but many initiatives imposed responsibility of redevelopment on NGOs, civil society organizations, and the government – and they fell short.

The opportunity has never been greater for increasing private sector involvement, through public-private partnerships with citizen engagement, to enhance economic viability for informal settlements, balanced with social and environmental responsibility and sustainability.

Formally linking government, residents, and private enterprise will help attract more investors and ensure that land is developed to increase its value, and will assure public consideration of broad community needs.

See Also: The world’s largest refugee camp: what is the future for Dadaab?

Brazil’s 1988 constitution grants favela residents up to 250 square meters of land they have occupied for five uninterrupted years, provided they do not own other land. Ownership can powerfully impact well-being in informal settlements, particularly if the process to formalize with physical (ideally, digitized) land titles can be streamlined on-site, with one-stop-shops. Land titles free women to leave home and seek jobs, rather than protect turf. Land titles also serve as loan collateral, and, if digitized, obviate the need for inspection visits.

Titles obviously are not a panacea and, for low-income applicants, should be accompanied by government programming and perhaps subsidizing of small loans and lines of credit. In some favelas, land titles have caused lower-income renters without rights to land to be priced out. Favela development must include affordable housing initiatives such as structuring incentives for developers to commit a percentage of units to low-income tenants.

The larger power of the land titles is that they are a financial instrument that can serve as shares in a cooperative. The cooperative can join the government and private sector in the public-private partnership, thus giving voice and escalated land value to favela residents.

Vesting land tenure and partnership rights in favela residents is a first vital step in improving quality of life. Brazil has a term with no English equivalent: jeitinho, which is creatively solving a problem (invariably illegally), with what one has. Favela-based residents are famous for having this skill, and making their communities work for them (and the city) despite the legal, technical, and financial difficulties. The challenge for stakeholders moving forward will be to improve the happiness of these residents and the wider city in ways that preserve the ingenuity of jeitinho, without the illegality.