By EMILY CAVAN LYNCH

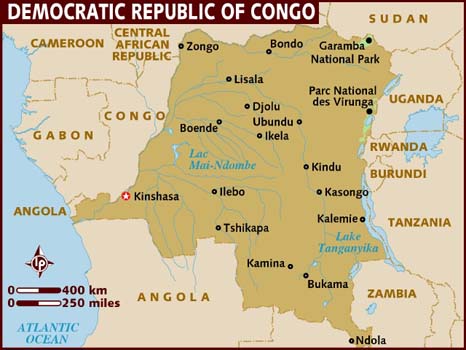

Emily Cavan Lynch, Global South Development Magazine’s country correspondent for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, also works for an international relief organization as a public health consultant. In this article Emily shares her everyday experience in the DR Congo and presents a holistic picture of a war trodden society that is struggling to overcome decades long trauma of bloodshed and killings, yet finds it caught up in new forms of unrest and conflict everyday.

Since 2009 Eastern Congo has gained a certain reputation. Through the well-intentioned efforts of caring individuals, the relief of organizations searching for a convenient way to define the muddle of armed groups and ongoing conflict, and the perpetual funder’s need to be able to measure progress, Congo is these days known to most in the developed world as the “rape capital of the world.” Last spring the American Journal of Public Health dropped the media bomb that the number of rapes per day in Congo had been grossly underestimated and was 26 times higher than a previous UN report had estimated, with at least 1,152 women raped every day (equal to 48 per hour).

This phrase and associated imagery has been the inspiration behind international advocacy and fund-raising efforts, documentaries and news features, the allocation of monies for bi-lateral donors, and the program strategies thus dictated to any number of NGOs funded by them.

- Line of Rape Victims in DRC

Yet it is an identity neither chosen (nor in most cases even known) by the majority of people implicated in its reach. It has also become something that certain organizations have grown to detest, watching it grow from one important voice in the dialogue to an overfed red herring of the system, distracting, in their view, the conversation from one that ought to be focused on a much broader scope of needs and causing, in some cases,far more harm than good (offer a woman who lives on less than $1 a day $60, or a $100 sewing machine, to testify that she was raped and see what you do for the perceived credibility of anyone else who has been raped).

The history and instability of Eastern Congo is generally framed as impossibly complicated; and in the need to address it, international actors are caught unprepared.

The donors of the current system of international aid are not think-tanks, philosophers or academics. They are program managers, lobbyists, bureaucrats and politicians with constituencies. They need a hat stand. They need a hook. They need it to be a sound clip, for goodness sake.

Stretched taught between the last civil war and something currently resembling stability, Eastern Congo is a funder’s dilemma.

In the system of international aid, implementors usually specialize in one of two categories: humanitarian organizations are called for when tsunamis wipe out an entire coastline, when 1 20,000 people flow into a refugee camp built for 40,000, when hospitals overflow with people starving or wounded, and when cholera floods into an already devastated country after a 50 year absence. Development organizations, on the other hand, come in when people are no longer fleeing for their lives, when schools are again open and kids can be given uniforms and books, when there is some sort of government or civil society framework to enable foreign organizations to do their work, and when their teams are not being hijacked, their bases are not being stormed by armed men, and there are no longer deadly skirmishes between armed groups.

These two categories of organizations have entirely different cultures, rules, capacities, funding limitations and paradigms. They  may partner with each other, and though they are often indistinguishable by those not working in the sector, they are in no way interchangeable, without inviting disastrous implications (see: Haiti after the earthquake or Indonesia after the tsunami).

may partner with each other, and though they are often indistinguishable by those not working in the sector, they are in no way interchangeable, without inviting disastrous implications (see: Haiti after the earthquake or Indonesia after the tsunami).

Following the political end to the most recent large-scale conflict in DRC in 2009, the world of international aid (e.g. the funders) decided that it was time to transition from an emergency intervention to a framework of long-term development, feeling that Congo was close enough to a kind of peace that the priority could change from flying in food rations and UN helicopters to supporting school fees, funding economic development programs and sorting out whatever residual trauma remained through piece-meal psychosocial programs.

Unfortunately, political resolutions do not always filter down to daily reality, and in this changeable world a resolution today does not dictate peace tomorrow. Eastern Congo is no longer considered to be in a state of full-out war. Rather, it has been in a state of low-to-moderate level conflict and instability , with a handful of villages pillaged every month, consistent waves of hundreds to thousands of people fleeing into ‘the bush’ out of fear of attack, regular targeted killings or skirmishes between armed groups, and one or two incidents of mass rapes (and yes, ongoing and pervasive sexual violence) every half-year or so.

With informed analysis and an ear to the ground, there is a certain amount of predictability. Where there are schools, most are still open. Some branches of the government function a bit. Most of the time you are not hijacked on the road. Outbreaks of preventable epidemics remain inexcusably frequent but people are used to their cyclical nature and take them in some amount of stride, keening for and burying their dead out of sight of most who can help, and out of mind of most who should be held accountable.

Who suffers the most?

The other day I conducted a focus group with representatives from various ethnic groups in North Kivu. We started off with an exercise about perceptions called “quick thinking,” where I asked them to tell me the first words that popped into their head when I mentioned several phrases beginning with “general population.” People said: beneficiary, displaced, sick or ill, vulnerable, victim. Then I asked for their associations with the word ‘in civique,’ which means something like “criminal” or “civil disturber”. They responded quickly: immoral, delinquent, rapist, assassin, bandit.Thefirstgroupofwordsare those with which we associate sympathy and empathy; we usually want to help the vulnerable. The second group of words are about actions and are framed in terms of blame and contradiction to a norm, encouraging the feeling that whereas the first group deserves our sympathy and help, the second group can be ostracized and blamed. After the exercise I raised these points and asked the group, but does this mean that the “inciviques” are not part of the population? Because of the diversified nature of the conflict in this region they most definitely are, and everyone immediately pointed that out, laughing as they did so at the obvious contradiction.

However it was a good reminder (and intended as such) that what we call someone influences how we feel towards them, and how we feel towards someone influences how we act, how far we go to help them and how much we do to hurt them.

In the Kivu region of Congo – where the majority of the conflict and instability is concentrated – it is in these names and underlying associations that we get lost. There are so many armed groups and their alliances, histories and loyalties so complicated that in general conversation we just call them this, “armed groups,” rather than trying to name them all. What we actually mean can range from members of the official Congolese army to a successful shopkeeper in some village who gives guns to a group of 1 9 year olds and tells them to rob a truck on its way to market.

One of the hindrances of the traditional vocabulary of war is that we talk about civilians and soldiers or armed actors as if they are clearly separated groups. The distinction is important (and considered a very useful thing) in terms of international humanitarian law; it allows the international community to agree on (and, more importantly, have a basis for prosecution based on) principles such as that of limiting collateral damage, meaning that a military strategy should avoid implicating civilians (e.g. if you must attack a village as part of an offensive strategy, you should not rape, pillage and murder civilians as well, but rather concentrate on the destruction of military targets or armed actors).

One of the hindrances of the traditional vocabulary of war is that we talk about civilians and soldiers or armed actors as if they are clearly separated groups. The distinction is important (and considered a very useful thing) in terms of international humanitarian law; it allows the international community to agree on (and, more importantly, have a basis for prosecution based on) principles such as that of limiting collateral damage, meaning that a military strategy should avoid implicating civilians (e.g. if you must attack a village as part of an offensive strategy, you should not rape, pillage and murder civilians as well, but rather concentrate on the destruction of military targets or armed actors).

As a humanitarian it is hard for me to accept that even this kind of dialogue is ultimately encouraging broad-scale respect of human rights but of course I can acknowledge that, within a limited viewpoint, the intention is there.

And yet, even with this benefit of the doubt, how do you apply such a precise framework to the definition of conflict in much of the modern world? In Eastern DRC, in addition to formal armies, you have a grassroots patchwork of what started as well-organized community militias who are not separate from the communities in which they live. They are not just “integrated,” in the common parlance; they are from the community. And perhaps they originally organized themselves according to ethnicity or place of origin or mother tongue, so now all who share that definition (whether bearing arms or not) are implicated by the consequences of their actions.

A community who “hosts” (whether or not they have ever been asked for their consent or opinion to do so) an opposition group is thus often considered a collaborator and may be free game for an attack. So in this way the armed groups ping-pong over the net of the population,moving in to and out of a community and then taking turns attacking the community for hosting the opposition group.

Of course it is true that in some places in the region people are living in relative stability. I do not say comfort or health, though this is of course also true in some areas, but stability. This means, first of all, that they can get to their fields when they need to in order to plant and to cultivate crops, and that they are able to stay in one place long enough to harvest them.

Much of Congo is covered with lush, fertile, productive land; there is no reason that anyone should go without food in this country, no reason that there should be stunting and micronutrient deficiencies and malnutrition common enough that you can walk through a village and point out all the children suffering from it.

This is not a given condition of life; this is a direct result of the choices made by those in power. Why should there be food insecurity in this region of Congo? For the same reason that people are dying from diseases like measles, malaria and upper respiratory infections. For the same reason that maternal and infant mortality in DRC is among the highest in the world: lack of access, lack of basic healthcare, lack of investment in things that benefit the population, like infrastructure.

The instability in Eastern Congo affects everyone. Access to crops ensures the link to a fundamental level of caloric intake and nutrition that is snapped like sugarcane the moment people feel forced to flee their villages. Even for places stable enough to harvest, the presence and passage of armed groups often means ongoing forced labor, unjust detention or bribery, frequent violence, and pillaging of goods and food. It may be that the armed conflict involves the participation of much of the general population (when there is no clear leader, how can there be confidence in the scattered leaders around?), but it also demands the suffering of nearly the entire population.

So who suffers the most? It is easy to say that it is children, women and the elderly. Yet in a landscape where fear is endemic,  suffering is also endemic; trying to live with a mentality where violence, hatred and domination are the only understood forms of survival is no way to live at all.

suffering is also endemic; trying to live with a mentality where violence, hatred and domination are the only understood forms of survival is no way to live at all.

Ongoing conflicts and future prospects Around the time of the presidential elections in November, rumors of cracklinginstabilityinDRCflewaround the world. The end of all hesitant peace was predicted; civil war said to be right around the corner.

At that time I was part of a rural vaccination campaign in the southern province of the country and during the week leading up to the vote itself a small team of us were progressing slowly up the lower Congo river in boats, vaccinating hundreds of children during the day in churches and shaded courtyards and camping each night in the mud yards of tiny health centers.

That week we also shared the river with puttering boats transporting voting boxes, election officials and the same gentian violet dye that we used to mark the pinkie fingers of all of the children who had been vaccinated already. Exhausted in my tent at night I had multiple confused dreams about putting used needles into the ballot boxes instead of election papers, and of accusations of fraud by election observers accusing us of marking the fingers of babies who were not even eligible for school, let alone for voting.

In the end, the elections passed by with a sort of peace truce, if not actually a set of comprehensive results. Since that time the international community has mumbled and grumbled and even published various official objections to dissociate themselves from what everyone generally now agrees was, at best, an inadequate electoral process.

But for a time afterwards it felt that if Congo did not have the 100% democracy that the Western observers were looking for, it might at least have avoided disintegrating again into civil chaos. And for those who live here, that was not an inconsequential result.

Unfortunately, in Eastern Congo at least, that feeling has now been replaced with a sense of apprehension. The elections provided a possibility that things might change; the disputes of the results maintained that sense of hope, leading some to think that perhaps, with all the international criticism the old political status quo might change; perhaps the politicians would put on new hats, and step up to the plates of their promises.

But, in truth, none of these hopes have materialized.

- Epulu River & Rainforest, Ituri, DRC

Traveling throughout North and South Kivu these days you get the most profound sense – not that it is being used as a proxy battlefield for competing interests (as might be presumed from the press) but rather that it has been largely abandoned. Controlled, oppressed, stifled and forgotten. In the North, baboons play on the roofs of the abandoned buildings at what used to be the entrance and stopover to Virunga National Park. Guards still lift the gate for vehicles to pass through but now, as you drive past them and wave, it is not with the expectation of seeing mountain gorillas; it is instead with worry about seeing armed guerillas.

But these sentiments have all been negative. What else of Congo these days? One surprising benefit to a country with such high levels of instability and under-development is that you do see, in precarious measure, a slight protective effect on the ecosystem. Of course you also see total destruction of ecosystems but at least where there no roads, the accompanying human chaos is also limited. Caught in mud up to our hub caps one day, I bent down to the shock of grasses that our guide had just cut through with his machete. In this random spot on a hillside in South Kivu, and without even searching, I saw more than ten insects crawling about and I heard a cacophony of others. Crunching, munching, crawling. It was an astonishing experience. (>> Continue Reading)

[…] DRC Diary: A Reflection From The Field. […]

[…] DRC Diary: A Reflection From The Field […]

[…] People Still a Target for Islamist Inquisitors in Bangladesh « Previous / Next » By thedevelopmentroast / June 14, 2012 / Asia, Bangladesh, Children, Girls, […]