The problem with mainstream international relations (IR) theories is that they are largely dominated by Western perspectives and Western school of thoughts. Global events, thereby, are almost always seen solely through the lens of the West. As a result, the voices of the rest, the concerns of the oppressed, are ignored and bluntly dismissed.

Dependency theory is one of the popular contributions of Latin American scholars and emerged as a critique of various Western perspectives, including the idea of modernisation and development as we know it.

From 1950s to 1980s, there was a wave of decolonisation throughout the Global South, and as a result, various newly-independent nations came into existence. Initially, these newly-freed and newly-formed states experienced rapid economic growth, better than that of 19th-century Europe. On the basis of these observations, it was believed that modernisation was a universal phenomenon, and by adopting and accepting it, these traditional societies could transform themselves into into “modern” and “developed” entities.

The fundamental problem with this argument was that development was directly linked to Western values and behaviour, and non-Western perspectives of development were ignore and negated. As Andre Gunder Frank noted in the sixties, most historians studied only developed Metropolitan countries and paid scant attention to the colonial and underdeveloped lands (Frank 1966).

A leading misconception that historical experiences of the developed and the underdeveloped were the same undermined the colonial experiences of the underdeveloped. Frank argued that underdevelopment is not a natural phenomenon, and contrary to the argument at the time, developed countries were not “underdeveloped” before they transitioned into development. In addition, Frank illustrated, on the basis of historical research, that underdevelopment was in large part the historical product of the past and a byproduct of the continuing economic and other relations between the underdeveloped satellite countries and the developed metropolitan countries. Frank argued that these relations were essential part of the capitalist system on a world scale as a whole. (Frank 1966).

Dependency theory emerged as a critically-evaluated counter Western perspective on the international system.

The core-periphery relationship in the international system meant the existence of a rigid division of labour on an international level where the periphery or the satellites supplied raw materials, cheap minerals and human resources to the core states. The core, thereby, functioned as a depository of surplus capital. The flow of money, goods and services into the periphery, and the allocation of resources were determined by the economic interest of the core (i.e. dominant states), and not by the economic interests or the need of the periphery (i.e. dependent states). In addition, the political and economic power was solely managed by the core, a concept which can be equated with the Marxist notion of imperialism.

So, dependency theory emerged as a critically-evaluated counter Western perspective on the international system, and scholars such as Theotonio Dos Santos, Raul Prebisch, Andre G. Frank, and Samir Amin contributed significantly to the domain of dependency scholarship.

In short, the central propositions of dependency theory were:

- Underdevelopment is a condition fundamentally different from development. Underdevelopment refers to a situation in which resources are being actively extracted and used for the benefit of the dominant/or the core, not for the poor in which resources are found (i.e. the periphery).

- Dependency theory advocates for a better and alternative uses of resources rather than complying to actions imposed by the dominant core states.

- Dependency theorists rely upon the belief of national economic interest which can and should be articulated for each country. The proponents of dependency theory believe that this national interest can only be achieved by addressing the needs of the poor and the marginalised.

- The diversion of resources overtime is maintained not only by the power of the dominant states but also through the power of elites in the dependent states. Dependency theorists argued that these elites maintained a dependent relationship because their private interests coincided with the interest of the dominant states.

The relevance of dependency thoughts in today’s world

Within the main theme of dependency, we can see several dependencies and inequalities in play – dependency in trade, in finance and in technology. As Dos Santos argued, “trade relationships are based on monopolistic control of the market which leads to transfer of surplus generated in independent countries to the dominant countries” (Dos Santos 1970:231). In that sense, the dependent countries became exporters of raw materials and primary goods, and were unable to compete with the core, developed states.

This discrepancy still persits today, in one form or another. For example, developing countries are still affected by tariff barriers. The prices of primary goods are decreasing in the global market which is affecting developing countries and their ability to develop.

Dos Santos already argued in the 1970s that in the dependency framework the financial relations are largely regulated by the viewpoint of the dominant countries based on loans and export of capital, which permitted them to receive interest and profit, engendered domestic surpluses and strengthened their control over the economies of the other countries (Dos Santos 1970:233). This is still what we see today.

Dependency scholars also argued that when developing countries opened their financial markets and integrated into the world economy, foreign capital controlled their economic resources and, rather than following a developmental strategy, a particular financial interest prevailed. This, too, is what we see in the contemporary global political economy.

Technological dependency is another important aspect in explaining global inequalities. Dependency scholars argued that the core had a technological monopoly that conditioned the periphery’s industrial development. The transfer of technology, if there was any, was more beneficial for the core countries as it protected their interests and left developing nations dependent on the monopoly of the core. It was, dependency scholars argued, too costly for developing countries to develop their own technology.

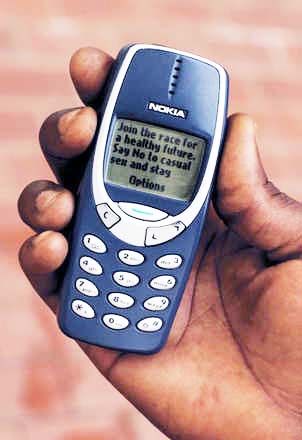

On some occasions, however, dependency limited the technology transfer to the periphery and dominant states only deposited obsolete technologies to developing countries generating a system of inherent industrial backwardness and dependency. This left least developed countries to rely on developed or developing countries’ new technologies as major technological innovations and gain in productivity largely occurred in developed countries and the least developed countries found themselves lagging and unable to compete in areas of new product development and production (Balaam, 2006: 336).

If we look at the amount of substandard technology and used digital products that is dumped in the developing world today, we can clearly see that propositions made by dependency scholars in relation to “technology transfer” still exists today. When it comes to valuable technology, be it digital or medical, developing countries are still largely dependent on the so-called core countries.

Dependency theory and the global financial crises

Karl Marx saw capitalism as a progressive historical stage that would eventually stagnate due to internal contradictions and be replaced by socialism.

If we take a close look at the history, we can see that human experiences of capitalism have resulted bitterly. We saw a huge slump in the form of the great depression in 1930 followed by the great recession of 2008, which is considered as the worst global financial crisis since the great depression. In the hindsight of the crisis of 2008, dependency theory provides an opportunity in explaining global inequalities.

The global financial crisis led to a decline of financial aid to developing countries, which further deteriorated their socio-economic problems, and eventually widened the gap between the global North and the global South. Secondly, since major financial institutions were controlled and regulated by developed countries, developing countries found it difficult to get access to capital whenever they needed.

As the 2008 financial crisis was on a full swing, Annan, Camdessus & Rubin wrote a piece in the Financial Times and argued for a “new global system of financial governance”, which should also involve more countries of the global south. “Poorer countries need a voice at the table, too”, they argued. This call for a stronger involvement of the countries of the global South in a new global system of financial governance, too, proves the relevance of the dependency perspective for understanding today’s global inequalities.

In other words, the financial crisis of 2008 showed the inefficiency of the global capitalist system and questioned the strengths of the new liberal economic philosophy in contributing to economic equality. Aaccording to Petras & Veltmeyer (2015) capitalism in the form of new liberal globalisation provides very poor model for changing society in the direction of social equality, participatory democratic decision making and human welfare.

Dependency and beyond

The problem with dependency thoughts is argued to be their tendency to overt generalization as dependency is not a clear and linear construct but something which is fluid and changes over time.

Originally, dependency theorists argued that the ideal way to break out of the dependency trap and global inequality is for the periphery to separate from the core, but the post Cold War era led to further integration rather than separation. We have also seen various examples that the separation from the core was not the key to resolving the issue of perpetual dependency and inequality global power structures.

When considering the role of the capitalist system in the underdevelopment of the periphery, the global financial crisis of 2008 provides an opportunity to contemplate the relevance of dependency theory in explaining global inequalities. One needs, however, to be cautious when using dependency theory as a generalized approach, as any disturbance in core countries will not automatically lead to a negative effect on the development of the periphery.

Like any other theory, dependency theory, too, has been admired and criticized, and naturally, it has its strengths and weaknesses. In today’s realm, dependency thoughts are still useful in analyzing the widening inequalities between the poor and rich countries, or in analysing the divisions within a developed or a developing country context. Our societies are vastly divided, and dependent relations exist within our own social facbric.

So, in the past, dependency thoughts broke some political boundaries and explained the reasons why wealthy nations were taking advantage of poor countries, and today dependency thoughts are useful in explaining recurring financial crises, the reckless use of natural resources and widening inequalities both in the global South and the North.

References used:

Annan, K., Camdessus, M. and Rubin, R., 2008. Amid the turmoil, do not forget the poor. Financial Times.

Balaam, D.N. Veseth, M. (2004) Introduction to international political economy, Upper Saddle River, N.J : Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Benabdallah, L., Murillo-Zamora, C. and Adetula, V., 2017. Global South Perspectives on International Relations Theory.

Farny, E., 2016. Dependency Theory: A Useful Tool for Analyzing Global Inequalities Today. E-ir. info.

Ferraro, V., 2008. Dependency theory: An introduction. The development economics reader, 12(2), pp.58-64.

Frank, A.G., 1966. The development of underdevelopment(pp. 17-30). Boston: New England Free Press.

Petras, J. and Veltmeyer, H., 2015. Power and resistance: US imperialism in Latin America. Brill.

Santos, T.D., 1970. The structure of dependence. The american economic review, 60(2), pp.231-236.

(Abdul Nasir is pursuing an undergraduate degree in international relations at The Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering, and Management Sciences (BUITEMS), Pakistan.)