by Ioulia Fenton

One of the hardest things to do for anyone interested in issues of environmental sustainability is to translate ideas and complaints into practical, positive, change-making action. For those who try to teach the next generation of environmental and social leaders in schools, in communities, or even online, this is even more important—merely talking about problems is likely to inspire only the students’ depression and frustration at lack of solutions. Luckily, Ecoliterate, a new book by psychologist Daniel Goleman and Lisa Bennett and Zenobia Barlow of the Center of Ecoliteracy—an organization that supports and advances education for sustainable living—is a deep well of ideas for those seeking inspiration.

The book is based on the premise that being successful at any endeavour requires more than a good IQ. Drawing on co-author Goleman’s seminal books, Emotional Intelligence and Social Intelligence, it explores the importance of developing the ability to manage one’s own emotions and maintain good relationships with others. It describes these capacities as key to improved academic success and the cultivation of ecoliteracy, which is the understanding and caring about the connections between humans and other aspects of the natural environment.The authors also introduce five ecoliterate practices:

- Developing empathy with all forms of life by recognizing that human being are not separate to the rest of nature.

- Embracing sustainability as a community practice involving other people.

- Making the invisible negative effects of environmental destruction visible for all to see.

- Better anticipating unintended environmental consequences of human actions.

- And a better understanding of how nature sustains all life.

See Also: Book Review: Geek Heresy

Believing that teachers “are ideally situated to lead a breakthrough to a new and enlightened ecological sensibility”, the authors spend the rest of the book taking an in-depth look at six eight real-life case studies that embody these five practices.

The first, for example, is a story of a community’s fight against Mountaintop coal mining in the Appalachians—a practice that has destroyed 500 mountaintops, 1mn acres of forest, and 2,000 miles of streams since the 1980s. The far-reaching, invisible effects of the mining were made visible to a group of students from Spartanburg Day School, South Carolina. The kids went on a “Power Trip” to Kentucky. The excursion contrasted an on-the-ground visit to a largely undisturbed, lusciously green part of the mountain range with an airborne view of fractured earth and sludge ponds of the heavily mined Black Mountain. The children felt such a strong emotional response from an innate empathy with the natural world that they were propelled into a range of practical actions, including publishing stories in local media and starting school and community-based environmental clubs.

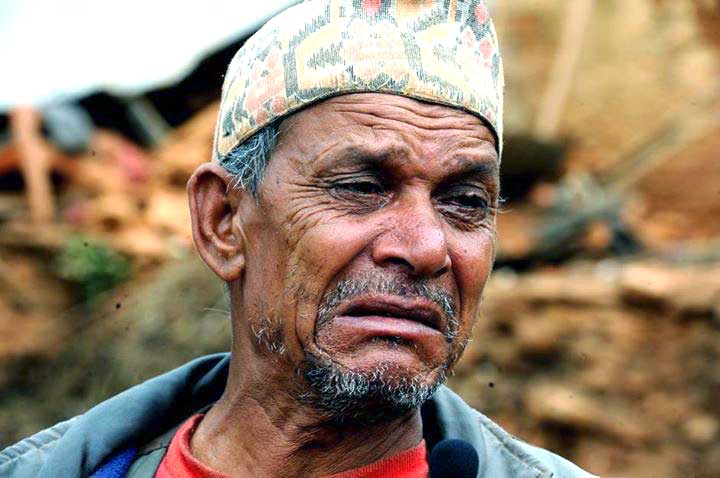

The third story tells the tale of the Gwich’in people’s resistance to oil drilling in Alaska—an intrusive practice that threatens to destroy the environment and their very way of life.

The fourth narrative talks about Kids Rethink New Orleans, a student organization that is fundamentally reshaping schools’ lunches, environments, and general sustainability for the better.

See Also: Story of a Rural Bolivian University

Next, the reader is introduced to Dr. Aaron Wolf whose research into cross-border management of common water resources, such as rivers and lakes, has shown that cooperation is best achieved when emotional, ecological, and even spiritual dimensions of importance of different parties are addressed.

Then the story of the Students and Teachers Restoring a Watershed (STRAW) program illustrates how, through emotional, social, and ecological intelligence, over two decades more than 30,000 kids have engaged in positive, ecosystem restorative action.

Through the tale of the La Semilla Food Center, Anthony, New Mexico—a grassroots organization that is leading the charge against obesity and hunger in local communities by forming Youth Food Policy Councils and youth farming opportunities—the reader learns how vital building connections can be in inspiring community-wide action.

These and two other stories carry powerful messages and inspiring examples of practical action taken by adults and children all around the United States.

Complete with lesson-planning guides for each chapter and a professional development plan, the book is written specifically for educators. However, it will strike a chord with anyone interested in sustainability. Aspiring and current activists and leaders will certainly draw from Teri Blanton—one of the main advocates against mountaintop removal mining—and her views on effective leadership: “don’t lead through anger,” she says, “reach people on a human level through stories, foster dialogue instead of debate, [and] speak from the heart.” Others would find truths in the words of Sarah James—an indigenous woman leading the Gwich’in (Caribou) people’s stand against oil development in Alaska—too. “There is nothing hard about it,” she says when talking about reducing, reusing and recycling, “there is nothing easy about it, it is something you do every day. And if everybody does it, it will become a way of life.”

Overall, Ecoliterate is a very timely contribution to a growing movement that is aiming to secure a sustainable future for upcoming generations. And because of the relevance of the grassroots case studies it covers, the myriad of inspiring wisdoms to be found in the words of the stories’ propagators, and the general accessibility of the writing, it is a must read for anyone interested in making or seeing a change from the bottom up.

Ioulia Fenton leads the food and agriculture research stream at the Center for Economic and Environmental Modeling and Analysis (CEEMA) at the Institute of Advanced Development Studies (INESAD) in La Paz, Bolivia.

This article originally appeared in the October 2012 issue of Global South Development Magazine that focused on inspiration.